In Temple Police’s main headquarters, there’s a dark room with an open floor.

The sound of shotguns, handguns and assault rifles can be heard through speakers, bellowing through the usual silence of the surrounding rooms.

Inside, the only source of light comes from a dim computer screen and a projector hanging from the ceiling. Behind the light of the computer screen, Officer James Jones cues a simulation of an active-shooter situation.

The police department practices these situations in alignment with the university’s exhaustive preparation for the possibility of a mass-shooting scenario on Main Campus.

“Shots fired inside the Pearl Theatre,” Jones says to his partner, Officer Damon Mitchell.

“It's another level of training. You have to get used to covering and protecting yourself, and that's the thing: We all want to come out of there alive.” Officer James Jones, TUPD

With his eyes on the projected image, Mitchell draws his assault rifle as five consecutive gunshots ring out. Two wounded computer-generations frantically run past him.

Four more shots fire as he nears the theater on the left. Mitchell keeps his gun—loaded with carbon dioxide which produces a life-like recoil in order to reinforce proper weapon handling for the officers—drawn toward the screen.

Silence ensues for 16 seconds, until the shooter emerges from one of the back aisles. Mitchell quickly opens fire and shoots at the screen multiple times.

“Show me your hands, show me your hands,” he says, but the suspect appears to be dead, and the projector screen goes black.

This is one active-shooting scenario of hundreds Temple Police can practice, with the hope they’ll never face the real thing.

Before the simulation begins, the participating officer chooses which weapons to activate. He or she can select handguns, shotguns, assault rifles, police batons, tasers and even a flashlight.

After the simulation ends, it displays the “hit zones,” of the officer, giving him or her an opportunity to analyze shooting accuracy with the pre-calibrated gun.

“It’s another level of training,” Jones said. “You have to get used to covering and protecting yourself, and that’s the thing: We all want to come out of there alive.”

This sort of training comes at a time when active-shooter situations on college campuses have become increasingly frequent. In 2015, there were 22 shootings on college campuses. The most prevalent example is the shooting at Umpqua Community College, an incident that left 10 dead and nine injured in Roseburg, Oregon Oct. 1.

In a more recent incident, multiple media outlets reported the University of Chicago canceled classes on its Main Campus yesterday after the FBI informed the school it had found an online threat, in which an unknown person said he or she was going to target “the campus quad” at 10 a.m. Monday.

Temple faced its own campus security scare this fall, when a 4chan post indicated a threat toward “a university near Philadelphia.” The FBI and the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives warned universities about the threat, and additional police officers were stationed at each university. The next day, the Community College of Philadelphia was placed on lockdown after an unrelated gunman was reported on campus.

The Temple News spent several weeks outlining the university’s contingency plans and measures of preparation in the event of an active shooter situation.

As an urban school with a police force with more sworn-in officers than some suburban police departments, Temple presents a unique set of challenges and resources to the table. With a plan developed over the course of decades, the university’s administrators have emphasized the importance of leadership, top-to-bottom preparation and trust in prior training in dire situations.

Through our reporting, we learned who handles major responsibilities in such preparation, along with how police and administration cooperate. Though there are nearly 100 buildings on Main Campus, facilities have similar contingency plans in case of an active shooter.

The business of 'worst-case scenarios'

Last Christmas, Sarah Powell bought Jim Creedon a book—one that reminded him of his father.

Amanda Ripley’s “The Unthinkable” analyzes individuals’ actions in catastrophic situations, and how those actions saved lives.

“Whenever my dad and [my mom] would travel, my father would make her learn where the exits were in the hotel,” said Creedon, the senior vice president of Construction, Facilities and Operations.

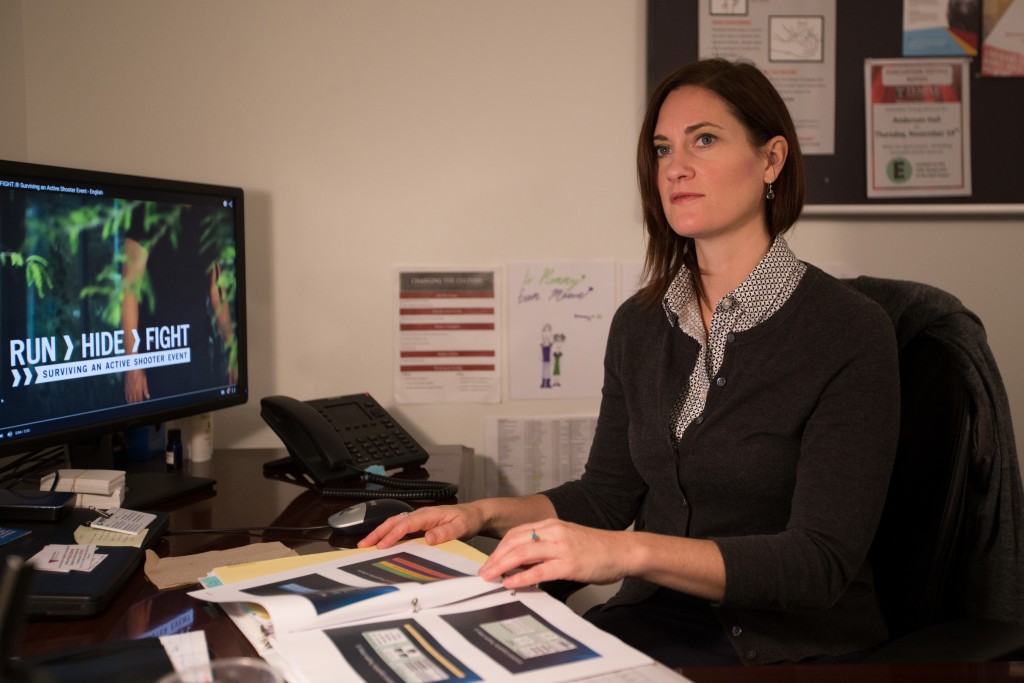

And Powell, the director of emergency management, takes on a similar role: She’s tasked with crafting the university’s contingency plans and prevention methods for anything from active-shooter situations to weather emergencies.

The level of scrutiny she brings to her position could be the difference between fatal situations and well-managed crises.

If you ask her colleagues, Powell doesn’t get much sleep.

“I do have a hard time not thinking about my job all the time because every single thing I’m working on needed to be done 10 years ago,” Powell said. “There’s a constant feeling of pressure to roll out the next step, to get the next thing in place.”

“We’re in the business of worst-case scenarios,” she added. “We never want to be caught not having planned.”

Powell has created a handful of policies and procedures in emergency management since taking over, and has taken part in the construction of three extra TU Sirens near the center of campus.

The sirens are designated to notify students and civilians walking outdoors on campus to seek shelter indoors immediately. Before the additions, the individual siren was inaudible from certain points on “the other side of campus,” Powell said.

Under Powell’s watch, there are now four sirens scattered around Main Campus.

Despite the emergency notification system, Powell said self-preparation for students can make the biggest difference in a crisis.

“I like to think about James Bond, or a superhero,” Powell said. “I want to be able to respond in that moment with a level of preparedness and training that in the absolute, extremely rare chance that it would happen, I would have at least thought through what to do so I can react.”

The Contact Team

Charlie Leone took his first job in Temple’s Campus Safety Services department in 1985. The system for active-shooter incidents then was simple: secure the perimeter, and wait for special operations.

Leone has played a large part in reforming that system and keeping with modern techniques to combat the possibility of an armed intruder on campuses.

Leone’s “contact team” is assigned the responsibility of first responders. Its main objective is to locate and neutralize the shooter.

“Years ago, it was the first responders that would go into the scene, establish the perimeter and wait for special operations,” Leone said. “In the meantime, people are being injured and killed. The newer philosophy with an active shooter is that everyone is trained. They’re all cross-trained. When we do our training, we rotate and rotate constantly, so that you may be a contact team, you may be a rescue team. ”

Leone and Powell team up to provide the police force—the largest university police department in the United States—with the proper training methods to ensure every officer is prepared for the possibility of confronting a gunman single-handedly as a part of the contact team.

As the first group on the scene pursues the shooter, the department establishes a perimeter around the building and assigns individuals to direct traffic, pedestrian flow and other logistical assignments.

Once the contact team fulfills its task of stopping the shooter and deems the area safe, another group of officers—the “secondary responders”—lead the effort of rescuing individuals inside and focus solely on facilitating people out of the area, giving priority to those injured.

From there, Leone and his colleagues call necessary assistance like Philadelphia Police, Philadelphia Fire Department and tactical groups.

The department trains in these scenarios multiple times a year, and expects to conduct a drill during the winter break, giving opportunities for adjustment. Its last active-shooter drill occurred in Barton Hall in June, which Leone said showed the strengths of the plan and also where police and administration could improve.

Leone and his colleagues had the chance to test their preparedness Oct. 5, when a post on a social media site threatened “a university near Philadelphia” days after the Umpqua shooting.

Security was heightened on Main Campus, as Temple Police posted a higher volume of police officers to monitor the situation.

“It was good because we can learn along the way,” Creedon said. “We can now make a note of what we need to adjust for next time, God forbid there would be an actual situation.”

“The threat scenario was so broad, however, we have a lot in place that we were able to do,” Leone added. “We were able to get the resources that we needed in order to not only make people feel safe but also be safe.”

Public Spaces Compared to Private Buildings

Despite the constant preparation conducted by Powell, Creedon and Leone, they still acknowledge the vulnerability of a public area like Main Campus.

“Trying to guarantee with 100 percent anywhere that you’re going to be safe is something that is next to impossible,” Leone said. “But we try to get as close to that as we can.”

Leone added one of the factors that helps university police prevent an active-shooter situation is more than 600 cameras scattered across campus, which are constantly monitored.

Powell said there are also emergency building managers designated to each building: key administrators dedicated to training staff on how to protect those inside a building during a dangerous situation.

“They know the facility and they know what to do, so we’re creating teams of basically floor marshals who know all of our procedures,” she said.

Jason Levy, senior director of Student Center operations, serves as one of these “floor marshals.” Levy said he and his staff train twice a year for emergencies like an active shooter.

Levy said three million people visit the Student Center annually, and 70 percent enter the main entrance on 13th Street near Montgomery Avenue.

“We know our building better than anyone else,” he said of his staff. “So we can respond to those emergencies quickly, efficiently, effectively, without panicking in a way that really helps the process for Campus Safety.”

The Student Center is one of the only buildings on campus that does not require identification upon entry. Levy said the most difficult aspect of preparing for emergencies in a public space is not knowing who is present, and he and his staff rely heavily on AlliedBarton security to monitor the facility.

Restricted-access buildings on campus are also guarded by AlliedBarton officers, who are required to ask for identification from those entering.

Leone said his department has hired 20 students to try and enter these buildings without identification. This “Quality Control Representatives” team, which started in Fall 2012, sends its findings to Temple Police, who then can examine problem areas and adjust accordingly.

“They’re the front line, so we’re going to need those folks to pay attention to what’s happening,” he said of AlliedBarton officers stationed in buildings. “If they’re not [checking identification], that leaves us vulnerable.”

Senior Vice Dean Diana Breslin-Knudsen and Managing Director of Faculty Affairs and Business Operations Rachel Tomlinson both consider themselves emergency building managers of Alter Hall, home to the Fox School of Business. Both said Temple is ahead of the curve when it comes to preparing for active-shooting situations, especially given recent incidents.

Breslin-Knudsen added that although Alter Hall is an academic building with restricted-access, there are many similarities to public buildings in how to prepare for an active shooter.

“The reality is that if you’ve got an active-shooter situation, it’s not going to vary that much,” she said. “You need to make sure people are trained, and what we’re working on now is how to best do the training with the students.”

No matter which building on campus, Powell said there are three methods to dealing with an active shooter.

“At the end of the day, you’re only doing a couple different things: you’re either evacuating, you’re sheltering in place because you can’t go outside because something is happening in the environment or you’re locking down,” she said. “No matter what your situation in any of these large-scale emergencies, you’re doing one of those basic things most of the time.”

Identifying Troubled Individuals

When the university’s attention was drawn to a threat from a social media post, Jim Creedon and his team organized a call in the middle of the night in October.

Several staff members were woken to participate in the communication between university officials.

Creedon said the volume of people on these emergency calls is often exhaustive but necessary to ensure no available information goes unshared.

“There’s no silos in our system that you often hear about,” Creedon said. “We have the late-night calls, and I feel bad sometimes about the people we’re waking up because they’re really not necessary for that particular call. But we’d rather err on the side of having everybody we need at that one moment on that call, so there isn’t that problem.”

The exhaustive inclusion of individuals aligns with Leone’s philosophy of extensively keeping an eye on situations before they could potentially escalate.

“Charlie’s part of a team of people who really do look at, ‘How do we identify people who are troubled?’” Powell said. “[He looks for students] who may be talking about things, who might be showing some behavior that’s problematic to their professors or peers. … They have an incredibly robust system in place for identifying and valuing and getting people help if they need it.”

In addition to meeting with Student Affairs and Tuttleman Counseling Services every week to review potential issues, Leone has a team of detectives capable of looking through social media for potential threats.

“We want to make sure we connect as many dots as possible, we all work together,” Leone said. “I have a group of folks who do a lot of the social media searching as well. So if we get wind of anything or if just by looking through some things that may pop up.”

Run, Hide, Fight

Even as policies and procedures surrounding preparation for active-shooter scenarios have evolved during the past few years, Leone still wants the training to be straightforward.

“You don’t want to be bogged down with a book this big of policies and procedures of one specific event,” he said. “What we want to do is get enough training, and when you think about the ‘Run, Hide, Fight’ from the Department of Homeland Security, it’s very simple.”

“Run, Hide, Fight,” penned in 2012, tells individuals in active-shooter situations to keep those three words in mind: “Run,” to escape or evacuate the area, “Hide” to seek a safe location and lock yourself from the shooter and “Fight” as the last-resort option—disarm the shooter by any means necessary.

Powell said the purpose of the phrase is to be simple enough that it becomes a second instinct for those involved in active-shooter scenarios, likening it to a similar phrase most students learn in elementary school.

“We all know what ‘Stop, Drop and Roll’ is,” Powell said. “If we’re on fire, which is sort of a scary thought, we know you drop on the floor and roll. … We would be able to react to that event, and just know what to do.”

Because the next few incoming classes will have become acclimated with the phrase “Run, Hide, Fight” in their middle-school years, Creedon said it will be easier to enforce as a safety policy.

In October, Temple Police uploaded a YouTube video detailing what to do if there was an active shooter in a building on campus, highlighting the “Run, Hide, Fight” method.

Breslin-Knudsen said the video teaches minor pointers, which could be the difference between life and death.

“It was interesting watching the video,” she said. “Because I never thought about turning off your cell phone, or putting it on silence. Because obviously, if someone’s walking around the building, and you’re hiding … an active shooter would know you’re in that space.”

Ultimately, no matter where an active shooter could be on campus, following the first step of “Run, Hide, Fight” is imperative for survival, Powell said.

“If you’re in a building where an active shooter incident is taking place, you need to get out,” she said. “Really, it’s about you at that point. It’s not about anyone ushering you out. It’s get out of the building, and get to a secure location.”

EJ Smith and Steve Bohnel can be reached at news@temple-news.com and on Twitter @TheTempleNews.

If you know anyone who may be troubled on Main Campus, contact Temple’s Wellness Resource Center at 215-204-7578. If you wish to report any suspicious activity on campus, please contact Temple Police at 215-204-1234.

Photos by Jenny Kerrigan, Margo Reed and Sean Brown.

Videos by Sean Brown and Abbie Lee.

Infographics by Donna Fanelle and EJ Smith.

Produced and designed by Emily Rolen.