Before the Fresh Grocer opened in Sullivan Progress Plaza in 2009, Quadralene Jefferson traveled from her home on 17th Street near Jefferson to South Philadelphia to buy groceries. The store was dirty, and she felt uncomfortable buying food there.

“I’m ordering meat, and I see mice running across,” said Jefferson, a home healthcare worker. “I couldn’t believe it, are you kidding me? You think I’m gonna still buy this?”

But it was her only choice for fresh food from a supermarket.

North Philadelphia is a food desert, which is an area where residents have difficulty accessing nutritious and affordable food, according to the United States Department of Agriculture. This affects the community’s physical and financial health, increasing obesity and heart disease rates while keeping people from purchasing sufficient amounts of healthy food.

Inflation during the COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated cost barriers to food access, as food prices at grocery stores increased by 6.5 percent between December 2020 and December 2021, according to the USDA’s 2022 Food Price Outlook.

Food deserts are rooted in systemic inequalities in urban planning, economic segregation, unequal economic investment and personal blame around nutritional intake. This issue is sometimes referred to as food apartheid to emphasize the discrimination that causes it, wrote Krista Schroeder, an assistant nursing professor and affiliated faculty member at the Center for Obesity Research and Education, in an email to The Temple News.

To properly assess and fight barriers to food access, the community must be involved in planning and implementing solutions so their needs, priorities and values are accurately accounted for, Schroeder said.

“All communities have strengths,” Schroeder said. “When addressing issues, whether it’s food deserts or something else, it’s really helpful to think about harnessing those strengths to work in collaboration to address barriers that they see as a problem to health and wellbeing, not just what others may see as a problem to their health and wellbeing.”

SHOULDERING THE COST

For Denis Maciel, a dancer at the Philadelphia Ballet who lives on Cecil B. Moore Avenue near 19th Street, the prices at grocery stores near him are higher than he wants to pay, so he often travels to Center City to shop at ALDI or ACME, where products are cheaper.

But commuting via SEPTA or Uber adds additional costs to his grocery trips, and he wishes there were more grocery stores in North Philadelphia so he could find better prices closer to his home.

“If it has more variety, like more grocery stores around, it would be better so you can have the option to choose by the price, like if you want it fresh, you don’t have to go [to Center City],” Maciel said.

Food prices in Philadelphia rose by more than 8 percent between 2019 and 2021 and are expected to increase for at least the next six months due to inflation and supply chain issues, 6ABC reported.

Fresh food in food deserts may only be available at prices that residents can’t afford, forcing them to purchase either unhealthier foods or not enough food, both of which make it difficult to maintain a healthy diet, according to the USDA.

Approximately 25 percent of Philadelphia youth get one serving or less of fruits and vegetables per day. Nearly 70 percent of youth in North Philadelphia are overweight or obese, which is nearly double the rate for youth in the U.S., according to the Center for Disease Control and Prevention.

North Central also has many characteristics of a food swamp, which is an environment saturated with unhealthy food items from corner stores and fast-food restaurants, Schroeder said.

Food swamps are associated with unhealthy dietary behaviors and obesity, and are correlated with communities that have larger low-income and racial minority populations, according to the CDC.

In 19121 and 19122, the ZIP codes surrounding Temple’s Main Campus, there are between 20 and 100 stores per 1000 people selling mostly unhealthy food options. Only zero to 10 stores per 1000 people sell healthy food like produce, according to a 2019 study from the Philadelphia Department of Public Health.

“There is some evidence that, even after accounting for whether someone lives in a food desert, that a food swamp may be the more salient risk factor, though both are important,” Schroeder said.

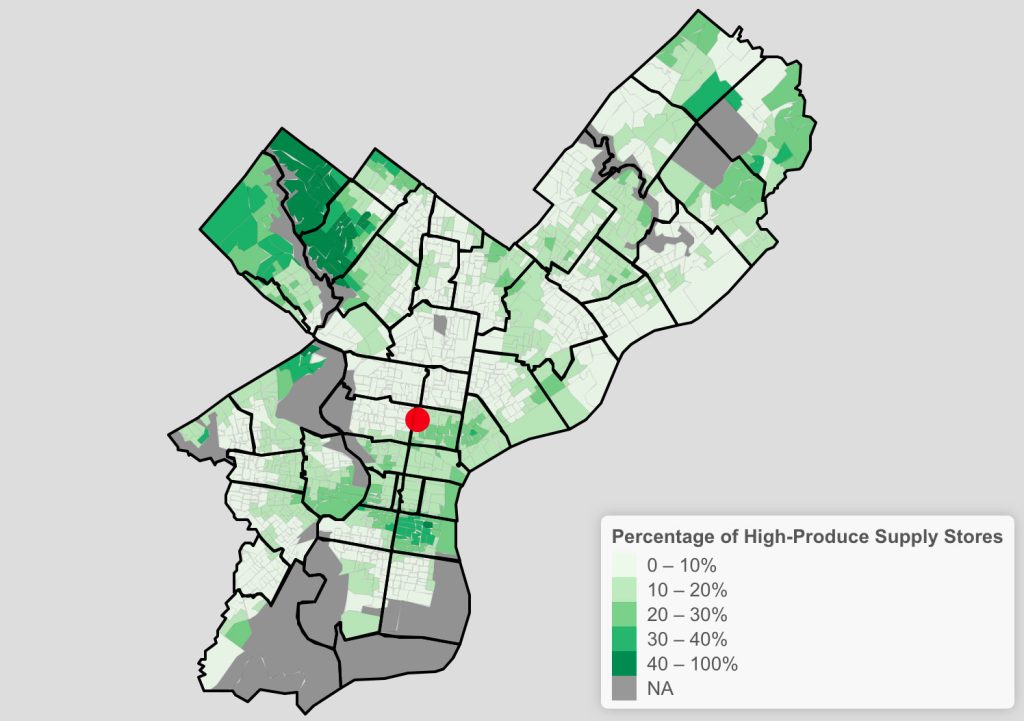

How healthy are the food stores in your neighborhood?

The greener the area, the higher the percentage of high-produce supply stores within a half-mile walking distance. The red dot represents Temple University.

Kelly Ballard, a security worker at Morgan Hall South who lives on 30th Street near Dauphin, has noticed there are more fast food restaurants near her home than produce stores.

“It’s not healthy, but it’s faster, so people gravitate towards it instead of going to the grocery store and making their own meals or healthier meals and trying to save some money,” Ballard said.

Products at her grocery store are often out of stock because everyone in the neighborhood is forced to shop at the same place, she said. She’s frustrated that better options haven’t opened in North Philadelphia.

“I definitely think they know what they put in different parts of the city,” Ballard said.

DECADES OF DISINVESTMENT

Food inequality stems from a history of disinvestment in communities, economic and resource segregation and systemic racial and socioeconomic inequalities, making it hard to support a healthy lifestyle, Schroeder said.

Philadelphia is one of the most segregated cities in the U.S. Redlining was a common practice in the 20th century when government and mortgage programs denied loans to African Americans, immigrants and Jewish individuals while classifying affluent, white neighborhoods as “ideal investments,” according to Philadelphia’s Office of the Controller.

Without municipal support, food retailers may move out of areas like North Central, further contributing to community disinvestment, said Hamil Pearsall, a geography and urban studies professor.

Supermarkets may also have little incentive to open a new store in an area experiencing high poverty rates because business may be perceived as less profitable, said Christina Rosan, a geography and urban studies professor.

Philadelphia is the poorest of the 10 largest cities in the U.S. by population, and much of that poverty is concentrated in North Philadelphia, where the poverty rate exceeds 45 percent in some areas, according to the Philadelphia 2021 State of the City report.

The U.S. poverty rate is 11.4 percent as of 2020, according to the 2020 Income and Poverty U.S. Census report.

While the number of supermarkets in an area is an important factor in assessing food deserts, the food available also needs to be desirable to residents, and people must feel safe and welcomed at food markets, be able to pay for fresh and healthy food items and have proper transportation, Schroeder said.

Jefferson is glad to now have The Fresh Grocer close to her home with fresh produce. It is convenient for her and her children to get food, and shopping there makes her feel welcomed.

“The people that work here, they actually help you,” Jefferson said. “You come in, ‘Do you need help with anything?’ And they direct you right to what you really want.”

A STRENGTH-BASED APPROACH

When discussing issues like food inequality, conversations often focus on what communities lack, but talking about what assets communities have to address food deserts can help identify meaningful and suitable solutions, Schroeder said.

“We also need to really work with communities to see these are the types of changes that are community-driven or empowered by the community, not just driven by folks who think that they know how to fix the solution as the outside experts,” Schroeder said.

The Food Trust is a Philadelphia-based national organization giving people access to food and information about healthy eating. They spearhead food justice initiatives in Philadelphia like the Healthy Corner Store Initiative, which stocks corner stores with healthy foods and provides support to store owners, and The Pennsylvania Fresh Food Financing Initiative, which invests in healthy food retailers and nutrition education programs.

“Access to healthy food is a human right,” said Caroline Harries, associate director of the National Campaign for Healthy Food Access at The Food Trust. “Families living in communities without healthy food options are missing out both on affordable access to nutritious food as well as the economic opportunities like jobs brought by healthy food access projects.”

The Food Trust collaborates with the city on many of their initiatives, but also allows perspectives from the community to guide its efforts by partnering with community members in planning and implementing projects, Harries said.

“It starts with a mindset that understands and prioritizes communities as having the most important perspective on what the needs are and where sustainable solutions lie,” Harries said.

The City of Philadelphia has goals to increase the number of businesses owned by food producers of color and create an Office of Urban Agriculture to support urban farms, according to the Philadelphia Food Policy Advisory Council’s policy recommendations for 2021.

Other goals include extending the moratorium on sales of empty lots hosting active urban gardens and purchasing food for city programs from small, local producers of color.

City initiatives effectively address food insecurity because the city has abundant resources to tackle large-scale issues, Pearsall said. But local action can empower residents, giving them jurisdiction regarding the changes being made to their community, like deciding what produce is grown in community gardens and ensuring they feel comfortable accessing food resources.

“For gardens that are being created and are anchored by a community in North Philly, then maybe that does provide a really awesome way for people to have greater food access,” Pearsall added.

It’s important to remember that many factors affect neighborhoods, families and individuals overlap to create food deserts, and no one solution will fix the problem entirely, Schroeder said.

“Just because you put a supermarket in and it doesn’t reduce obesity and reduce heart disease and reduce hypertension, it doesn’t mean it’s a bad idea to put a supermarket in a neighborhood, it just means that it’s just one piece of the puzzle,” Schroeder said.