With a gun pressed to his stomach, Evan Mallon offered up all of his belongings: his phone, wallet and bags packed with clothes.

“Give me everything,” he was told.

The man he encountered at 16th and Oxford streets took the phone and searched through Mallon’s coat before moving on. Mallon was on his way to a beach trip on the first night of Spring Break when the incident occurred.

“You’re not going to do anything,” Mallon, a senior art major, said. “You’re not going to scream, you’re not going to do anything that this guy doesn’t tell you to do, because it is life and death at this point.”

The armed robbery was the second incident for Mallon this school year – he was thrown into a fence and suffered a cut to the head last December.

While Mallon said he brushed off the first incident as a random case of wrong place, wrong time, the second, more recent incident stuck with him.

“I came to Temple being like, ‘It’s not going to be as bad as you think,’” he said. “No one is out to rob anyone for the sake of just robbing them.”

That notion, Mallon said, was thrown out the window the night the man absconded with his phone.

“You’re not going to scream, you’re not going to do anything that this guy doesn’t tell you to do, because it is life and death at this point.” Evan Mallon, Senior

Mallon said the suspect also robbed another student of his phone at gunpoint, as that student was walking with a friend about a half-block behind Mallon on Oxford Street at the time of the incident. Both victims soon called police.

They received a quick response and were taken around neighboring streets to other police cars who had stopped men that fit the students’ description.

Since the robbery, Mallon said he mostly stays at his girlfriend’s apartment, which sits closer to Main Campus. He rarely goes to his apartment on 18th and Oxford streets, two blocks farther off Main Campus from where he was stopped. If he needs to, he said he usually bikes or skateboards – he feels wheels make him safer than walking.

“It really made me so overly cautious,” he said. “Almost to the point of prejudice.”

Mallon’s feelings highlight one of the most pressing issues facing the university community – campus safety. During a period in which Temple’s footprint seems to be expanding farther and farther beyond the confines of Main Campus as the university continues its transition from a mostly commuter school to a largely residential one, crime in the area is a major cause of concern for students, parents and community residents.

A series of recent high-profile incidents have heightened these concerns. In October 2013, a professor was robbed at knifepoint inside his office in Anderson Hall. Last October, six students were tied up and robbed in their home on the 1900 block of 18th Street in a targeted, drug-related attack. In January, 56-year-old community resident Kim Jones was murdered at 12th and Jefferson streets, and surveillance footage captured the alleged killer, 36-year-old Randolph Sanders, walking through Main Campus. Robert Wilson, a Philadelphia police officer from the 22nd district, which encompasses Temple, was shot and killed at a GameStop northwest of Main Campus in March, which also brought attention to the area.

Perhaps the most highly-publicized recent crime happened on an evening in late March 2014, when four students said they were victimized in three separate assaults by a group of about 10 youths. One of the beatings, carried out with a brick, left a female student in the hospital requiring emergency surgery.

In the immediate days that followed, each of the students said they attempted to go to the police to report the incidents, but only found varying degrees of help. The university did not send out a TU Alert – the text and email notification system that the university maintains is meant to inform students of ongoing incidents in which there is an “immediate danger” to the community.

A then-15-year-old girl was later arrested, charged as an adult and sentenced to two-and-a-half to six years in state prison, along with four years of probation and other conditions.

The “brick attack,” as some have called it, sparked the university’s expansion of its patrol borders during the fall semester last year. Since the victims notified Philadelphia police first and the incidents took place beyond the Temple Police patrol zone, Temple officials were not immediately aware of the attacks and did not make a statement until three days later.

“I think that kind of hit home and said, you know, we really have to take another look at this,” Executive Director of Campus Safety Services Charlie Leone said following the patrol border expansion.

Temple Police broadened its patrol zone by nearly 25 square blocks, mostly extending its boundaries to the west and southeast of Main Campus. The announcement was met with positive feedback from students.

While theft and robbery are among the most common crimes to occur at Temple, sexual misconduct has also been a problem – as police say reported incidents rose during 2013 and 2014. Last May, Temple was announced as one of 55 – now 94 – colleges and universities under investigation by the Department of Education for possible violations to Title IX requirements in relation to the university’s handling of sexual assault and harassment cases.

Still, in terms of overall offenses, Temple manages to maintain comparable statistics to other major higher education institutions throughout the city. The total number of crimes reported on Main Campus was 600 in 2014, the most recent available statistics distributed under the Pennsylvania Uniform Crime Reporting Act. This figure ranks second of six local universities – which includes the University of Pennsylvania, Drexel, St. Joseph’s, Villanova and La Salle. Penn recorded the most offenses in 2014 with a total of 1,030, much of which is probably the result of a larger patrol area compared to the other universities, Leone said.

The respective police departments of each school listed above declined to be interviewed for this story. President Theobald, whose tenure began in 2013, also turned down an interview request.

To combat robbery, theft and other crimes, the university community relies on Campus Safety Services – a department that employs more than 130 sworn Pennsylvania-certified police officers and several building security guards. According to multiple sources, Temple Police is the largest university police force in the country.

Though Temple’s police department has existed for several decades, it has evolved with the school that it protects. Facing dynamics unlike many other universities, like tense relationships between new students and longtime residents, along with the school being located in one of the most crime-ridden areas in the city, Temple’s officers face many obstacles in keeping Main Campus safe.

The Temple News has spent the spring semester reporting on these obstacles, and the methods Temple Police uses to overcome them in an effort to protect the university community. Through interviews with more than a dozen students, officers and community leaders, reporters here have aimed to tackle an often-asked question – one that comes to mind for many current and prospective students, along with their families and surrounding neighbors: How safe is Temple University?

Charlie's Folks

During an early Saturday morning last November, Charlie Leone received a phone call that he said “made his heart stop.” A Temple student had been shot.

As he soon discovered, a bullet struck a 22-year-old undergraduate in the left hip outside of the Pi Lambda Phi fraternity house on the 1500 block of North 17th Street.

The student was lucky. The injuries, not life-threatening, were treated at Hahnemann University Hospital and resulted in a quick release from the medical facility.

Even with more than 30 years of involvement with Temple Police, Leone said whenever a student is involved in a serious incident like the shooting last November, it’s a scary situation – especially for the victim’s parents receiving the call.

“I’m a parent,” he said. “So from the parent’s perspective, I’m like, ‘Oh, I can’t even imagine as a parent getting that phone call.’ And then as executive director, I’ve got to put on that suit and talk about what we need to do, what we need in the community … so that’s a heart-stopper.”

Leone, the executive director of Campus Safety Services, is in charge of the the largest university police force in the nation – a team he calls “his folks.”

Temple, an urban university that sits in a richly-historic North Philadelphia neighborhood, does not have defined campus borders. And, given its location, the university also has a high crime rate – according to Temple’s 2014 Security and Fire Safety Report, nearly 1,300 crime cases were documented in 2013, the most recent university data available.

On a day-to-day basis, Campus Safety Services collaborates with the Division of Student Affairs, offers shuttle and walking services and provides general information and tips for students to remain safe on and near Main Campus. CSS also offers self-defense classes through the university and hosts numerous events to promote campus safety.

Throughout Main Campus, there are about 60 blue emergency phone poles that serve as a direct line to Temple Police in case of an emergency. The university’s main notification system, TU Alert, sends an email and text message to registered students and employees when an incident occurs on or near Main Campus that requires “immediate action,” according to Temple’s Annual Security and Fire Safety Report.

Students critical of the system feel it isn’t consistent with releasing information, but Leone said the alerts are only for incidents that pose an immediate threat to the entire community, so not all cases of serious crime will be shared. The limitation of alerts is partly aimed to prevent unnecessary fear among the student body.

The presence of bicycle cops has also broadened the capabilities of Temple’s police force. The university has a contract with AlliedBarton Security Services, which is designed to provide another layer of protection in buildings, and has a strong relationship with Philadelphia Police’s 22nd District, which includes Temple. SEPTA Transit Police Chief Thomas Nestel III spoke highly of his department’s alliance with the university, citing classes it offers to Temple Police officers on how to navigate tunnel systems.

Bicycle officer James Jones, who has been a part of Temple Police for seven years, spends nearly five hours a day on his department-provided bicycle, biking up to 15 miles in a day. Jones’ routine, which begins at 7 a.m., includes biking to 10 different checkpoints through Main Campus, directing traffic and sometimes being the first responder to a crime scene.

“We respond to it all, everything is fair game for us,” Jones, who carries a radio and a firearm on him while taking his rounds, said. “Depending on what the job is, sometimes we’re first to the scene. If there is an arrest that has to be made, we’ll call in an officer with a vehicle.”

Jones said the bicycle officers from private security contractor Allied Barton serve as TUPD’s eyes and ears, but do not carry weapons.

“They can only do so much,” Jones said. “They have to report what they see, they don’t carry weapons, and that is a big disadvantage. They are truly an extension of us, they’ll call us when they see things. … It’s a layer, another layer of security.”

Even with a high volume of patrolling officers, certain types of crimes remain an issue. One in particular is sexual assault, which has received national recognition with the launch of President Obama’s “It’s On Us” Campaign this past September.

About two months after Obama’s announcement, the U.S. Department of Education’s Office for Civil Rights visited Main Campus and led focus groups concerning a Title IX investigation that was announced last May for the university’s handling of sexual violence and harassment complaints.

According to Clery statistics from Temple’s 2014 Security and Fire Safety Report, the number of total sex offenses has increased on Temple’s Main Campus from 2011-13. The total dropped from seven to four from 2011-12, before rising to 11 two years ago. Leone said that number continued to increase in 2014, even with more attention toward these incidents.

But compared to other major area universities – La Salle, the University of Pennsylvania, Drexel, St. Joseph’s and Villanova – the Pennsylvania Uniform Crime Reporting Act shows that although the number of sex offenses have increased, Temple ranks lowest when accounting for discrepancies in students and employees while using Clery statistics.

Based on the state’s Uniform Crime Reporting formula, which uses a 100,000-person index divided by each university’s number of “full-time equivalents” – the combined total of full-time students and employees – Temple had a crime index of 32.7 for sex offenses in 2013. St. Joseph’s, La Salle and Villanova all had figures that roughly doubled Temple’s.

However, even with more information available about the crime, Leone said sexual assault continues to be underreported, which could affect the statistics for each university.

In contrast, Temple ranks comparatively high in overall robbery cases when using the same 100,000-person index. In 2013, the university reported an index of 77.3, trailing only Drexel University, which reported an index of 85.8.

Leone said at least 80 percent of robberies on Temple’s Main Campus involve cell phones, because they’re easy to steal and have a high transfer value.

“It’s so easy to come by and grab it out of your hand and run,” Leone said. “It’s an opportunity crime … it’s an easy thing to take, so that’s what we’re seeing.”

A similar offense – theft, which is not classified as a Clery crime – also remains an issue. Crimes that fall under the Clery Act are “incidents that occur on campus, in unobstructed public areas immediately adjacent to or running through the campus and at certain non-campus facilities,” according to the Act’s website.

Donna Gray, manager for Risk Reduction and Advocacy Services at Temple, started a theft-reduction program in 2010, which involves student workers placing Temple Police stickers on items left unattended for extended periods of time in high-traffic university buildings. She said the program is important because theft continues to be a problem on college campuses.

“People may not think it’s that big of a deal,” Gray said. “But the reality is, whatever you purchase, it’s costing you something, and replacing it is costing you something. In terms of a criminal enterprise, why should people profit from that?”

In terms of another major Cleryy crime, aggravated assault, Temple ranked fourth among the six schools with an index of 20.8. Villanova placed highest with an index of 33.3.

Clery and Uniform Crime Reporting Act statistics for the 2014 calendar year will not be available until October, because of changes in Temple’s Annual Security and Fire Safety Report, Leone said.

“Part of the problem is that laws are changing,” Leone said. “When laws change, you have to change your documents … it’d be easy if the only thing you needed to publish was your crime statistics … we could do that by the end of January.”

Leone added that Temple Police pulls this data and information from multiple organizations and sources, further slowing the process.

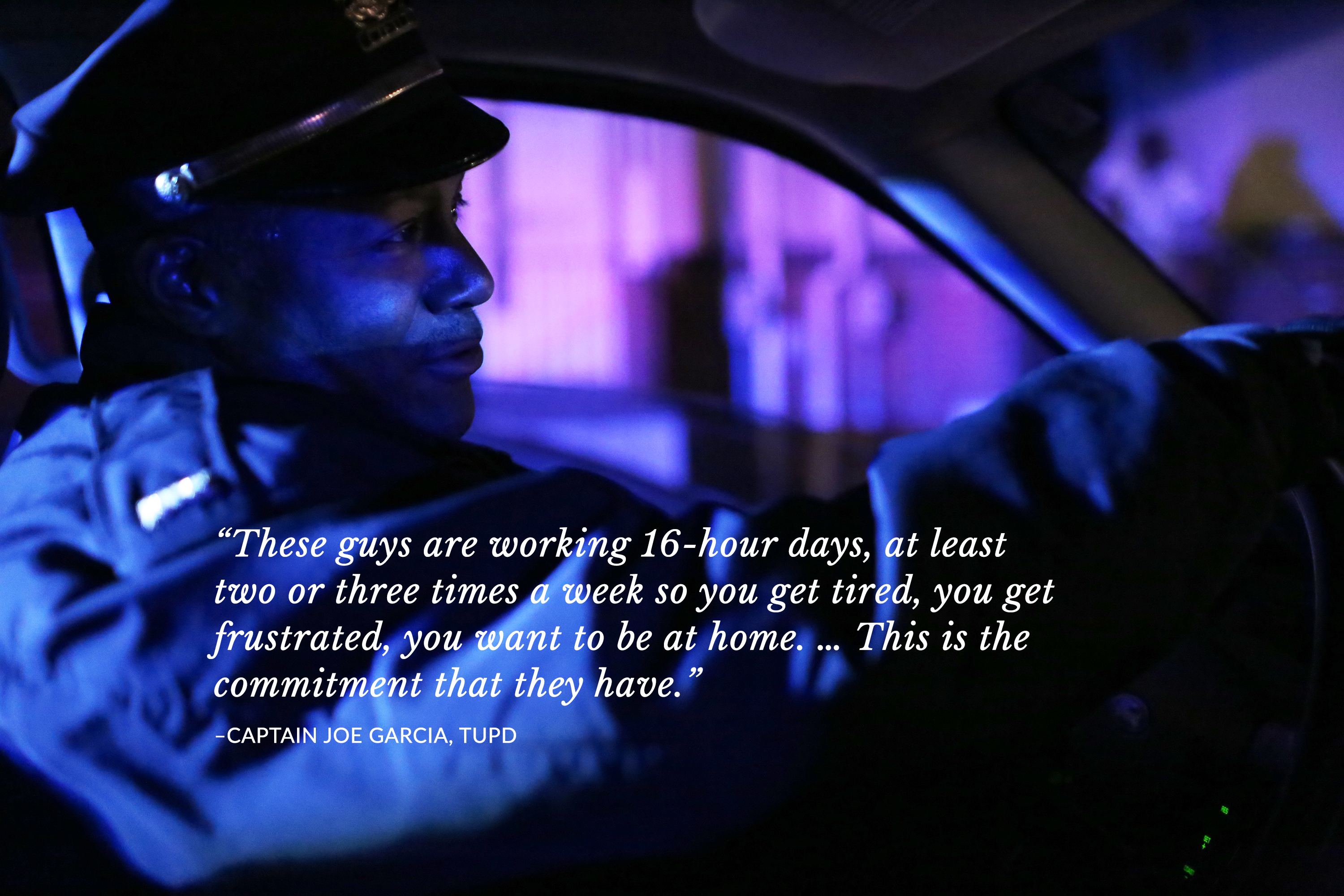

A key part of maintaining and updating these documents and statistics – along with a strong security presence – is communication. Captain Joe Garcia, the head of Temple’s Communication Center, was asked in 2010 to come in and help “professionalize” the department.

“We knew that 24/7, 365 days, our communication center would have to be committed to providing the service that they needed to provide to the community,” Garcia said.

Temple has had a communication center since 1968, albeit a simple one, with one person operating a single phone, Garcia said. Now, the center is operated by a shifting four-person team of dispatchers who have to go through a rigorous, multi-step training and development track.

This process helps the dispatchers when using the available technology which includes live-feed monitors from more than 600 cameras around Main Campus and the CAD, or computer-aided dispatch, system that opens and automates lines of communication between Main Campus and the Philadelphia Police Department.

Garcia holds deep praise and trust for his team, which he said deals with stressful situations every day.

“These guys are working 16-hour days, at least two or three times a week so you get tired, you get frustrated, you want to be at home,” Garcia said. “It’s a 24-hour operation, so we have to cover it. … This is the commitment that they have.”

From ‘guards’ to officers

Early in his time at Temple, James Hilty’s employment would draw some stares. “There were times when Temple was a difficult place to come and go to,” Hilty, a former administrator and historian at the university, said.

“When I told people, ‘I work at Temple,’ they’d sometimes say, ‘Oh my,’” he added.

Friends, relatives and others he met largely knew the university as a dangerous place, particularly after one notorious incident, in which a student was murdered in a parking lot on Main Campus.

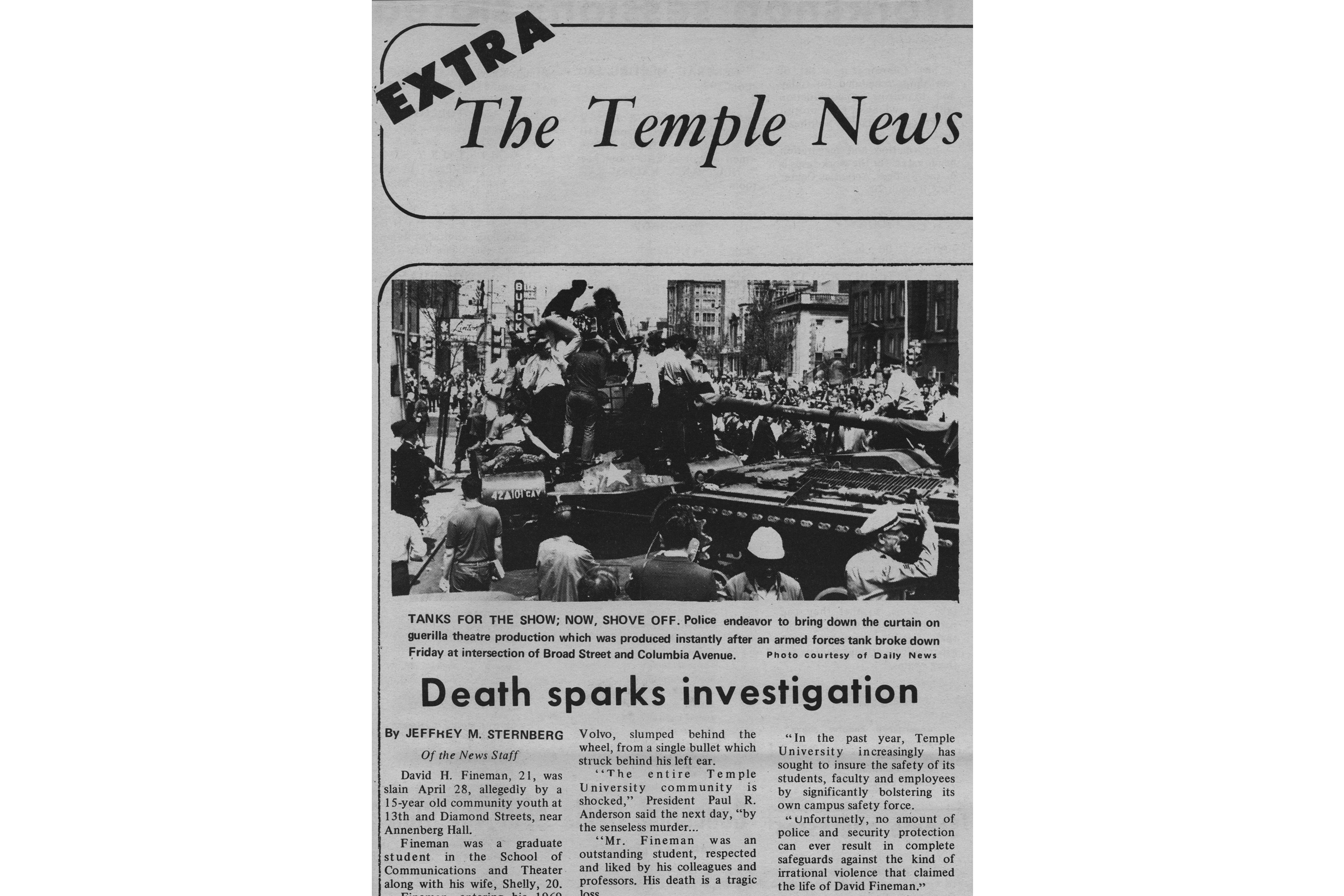

David Fineman, a 21-year-old graduate student who taught junior high in Ardmore, was shot and killed in late April 1970 outside Annenberg Hall after presenting a paper there.

Police apprehended several young men who lived west of Main Campus in connection with the shooting. Several of their addresses, mostly on Bouvier Street, are now surrounded by student residences.

Homicide Lieutenant James Murray told the Inquirer the suspects “were out to to get anybody, to kill someone, with no particular person in mind.”

The murder “gave Temple some bad publicity,” Hilty said. And that included the front-page, two-story package in the April 28 issue of the Inquirer, in which Murray is quoted.

The media attention led to Marvin Wachman, then-vice president for academic affairs under President Paul Anderson, addressing Fineman’s murder and another crime on the Health Sciences Campus in a letter to the Temple community dated May 1, 1970.

“These senseless incidents have shocked the University community and its neighbors, but they have also raised questions about the effectiveness of present security arrangements,” he wrote.

The university then convened two task forces, one for each campus, which were required to provide recommendations for improvements to campus safety no later than May 15 of that year.

Several of the task forces’ broad recommendations, outlined in a May 20 story in the now-defunct Philadelphia Evening Bulletin, are now a reality for students today, including emergency phones and university-wide photo identification.

Around that time, Temple was beginning to expand out farther from its base east of Broad Street, buying up properties and clearing land in a neighborhood which had changed drastically since the post-World War II era.

Around 1945, North Philadelphia began to de-industrialize. Once a haven for the garment and textile industries – many neighborhood residents walked to work at a factory near their home – companies began to move out of the city in favor of places farther south in the country.

“Workers moved out because companies moved out,” Hilty said. Many followed their employers.

That shift resulted in housing vacancies and a changing neighborhood as poorer ethnic groups moved up from the south, part of the Great Migration.

“The whole pathology of North Philadelphia changed,” Hilty added. “You can’t blame it on a single fact. The people that moved in just weren’t able to sustain that quality of life.”

And with the changed neighborhood, larger campus and recent incidents in mind, Temple began to recruit more officers, including a significant portion from the city force, while professionalizing and standardizing its own.

Captain of Special Services Eileen Bradley, who joined the department in 1972 as its first female patrol officer, said Fineman’s shooting led to a “hiring spurt,” of which she was an initial part.

“Back then it was just the night shift [that was armed],” Bradley said. “And you didn’t bring [your weapon] home, you had to turn it in every night.”

Bradley said that at the point she was hired, the force was relatively large for the area.

“You could have a police officer on every corner,” Bradley said. “Of course, there weren’t that much [corners]. We didn’t go beyond 12th Street. … The footprint was smaller.”

Bradley was also the first officer to patrol on a bicycle.

Enlarge

“We had these Schwinn red bicycles,” she said. “I loved it. … It was strictly a volunteer thing, and I volunteered for it. I could get anywhere on this campus faster than anybody else.”

One challenge that arose in long-term plans to deter crime was that Main Campus was left open, Hilty said. Other schools rising in deteriorating areas, including Yale and the University of Southern California, “basically put up walls” to deter crime, he added.

Columbia University, near New York City’s Harlem neighborhood, kept a more open campus as its surrounding neighborhood deteriorated, and has had struggles with crime.

“I’m grateful Temple hasn’t built up walls,” Hilty said. “We’ve kept the campus open to the community. Anyone can walk through it if they’d like.”

Through the 1980s and 1990s, the university continued to hire officers and the newcomers were regularly touted in administrators’ speeches and letters as well as campus safety pamphlets sent to parents and prospective students, particularly after President Peter Liacouras announced his “Zero Tolerance for Crime” initiative. That plan included more visible foot patrols and increased use of technology, along with more hiring.

“I’m grateful Temple hasn’t built up walls. We’ve kept the campus open to the community. Anyone can walk through it if they’d like.” James Hilty, Temple Historian

Announcements of new hires from that era indicate that several new officers had previously served as building security guards. And under Liacouras, the school also created new administrative positions for campus safety, recruiting candidates with experience in the Philadelphia Police Department, including a former deputy commissioner and a former Inspector.

The facilities for Campus Safety Services, as it is now called, included a locker room on Norris Street where the Edward Rosen Hillel Center stands, and the small office across from Sullivan Hall on Polett Walk. There were some additional offices in what is now the Conwell Inn.

As Bradley remembers it, the expansion of the force necessitated the move to the Bell Building, a former operations center for the Bell Telephone Company that now houses CSS and the TECH Center. At first, Temple rented out the building from Bell, but now the university owns it.

Captain of Security Operations & Special Events Jeffrey Chapman, who has served since 1986 and earned his bachelor’s degree in criminal justice at Temple last year, said there were still changes to be made under Liacouras to continue professionalization.

“I remember, once upon a time, we were strictly referred to as guards,” Chapman said. “As time went on, we made some changes and got into community policing, started developing relationships with the community and the university, and got to upgrading the equipment.”

He said the difference between the department then and now is “night and day.”

In the 1990s, TUPD changed its uniforms to the current color scheme — “something more professional,” Bradley said, was changing the primary color from gray to midnight blue — and a young Leone modeled the new uniform in an announcement flyer on the change.

In more recent history, the force has expanded its use of technology, including use of the blue emergency phones installed in 2001, and has expanded bike patrols while increasing hiring, particularly in the years leading up to the expansion of the patrol borders west to 18th Street and as far south as Jefferson Street.

Several officers who began serving around 30 years ago, including Chapman and Bradley, are still on the force and have watched it change through the years.

“I think we’re all proud to wear our uniforms and proud to be where we’re at, because it wasn’t always like this,” Chapman said. “We didn’t always have positive feedback, we didn’t always have positive, good relationships, even with the university. … Everyone didn’t look at us the same.”

a place to call home

Once, it was a game.

More than a year has elapsed since teenager Zaria Estes and a group of accomplices patrolled the streets along the outskirts of Main Campus, looking to, as a prosecutor would later say, “knock a bitch down.”

Zaria Estes, 15 at the time, grabbed a brick and hit a 19-year-old student in the face who was walking home slightly west of Main Campus – it was March 21, 2014 at about 6 p.m., around dinner time. The sun was still out.

That student was sent to Hahnemann University Hospital and required emergency surgery. Assistant District Attorney Paul Goldman said the group saw a few girls on the street and asked if they wanted to join in on the attacks, resulting in three assaults within a five-block radius. No TU Alert was sent for the incidents and the students who reported the assault to Temple or Philadelphia police said they received varying degrees of help.

Estes was sentenced to a minimum of two-and-a-half years in prison and four on probation after pleading guilty to aggravated assault, conspiracy and possession of an instrument of crime with intent to harm.

For Temple Police, the incident was a wake-up call.

“I think it certainly had us ask the question, ‘Are we doing everything we can to provide a safe environment for the students?’” Executive Director of Campus Safety Services Charlie Leone told The Temple News last September.

“We wanted to think of it as a good way to be supportive to the students, supportive to the neighbors and then showed them that we can be a cohesive community and make the whole place safer,” he later added.

Since the attack, Temple Police has expanded its patrol borders significantly. Last fall, the western boundary was extended from 16th Street to 18th Street, a notable change that affects students living past 16th Street. Other changes included extending the eastern boundary to Ninth Street, the northern boundary to Susquehanna Avenue and the southern boundary to Jefferson Street. The number of TU Alerts sent out by the department has increased as well.

Since the attack, Temple Police has expanded its patrol borders significantly. Last fall, the western boundary was extended from 16th Street to 18th Street, a notable change that affects students living past 16th Street. Other changes included extending the eastern boundary to Ninth Street, the northern boundary to Susquehanna Avenue and the southern boundary to Jefferson Street. The number of TU Alerts sent out by the department has increased as well.

Still, despite the flood of concern following Estes’ violent attacks, the new safety precautions don’t ease everyone’s mind. Evan Mallon, the student who was assaulted and robbed in two separate incidents during his collegiate career, said his continued exposure to danger and feelings of insecurity have impacted him in a way he didn’t think possible when he first stepped on to Main Campus.

Mallon is from Wyomissing, Pennsylvania, and acknowledged Temple’s reputation for crime when he enrolled. He said that he thought he would do what most people tell Temple students to do – “be smart.”

Evan Mallon, senior visual studies major, has been assaulted twice. The second assault took place on 16th and Oxford streets where the armed robber took several of Mallon’s belongings, including his phone.

“I’ve gone to Temple for the last three years and have been totally fine with the impression that crime happens anywhere,” he said. “But having something like this happen twice in a recent time span has really just freaked me out.”

Prior to both of Mallon’s experiences, several Temple students were tied up and robbed of a few thousand dollars worth of personal property last October in an off-campus home invasion on the 1900 block of 18th Street, between Berks and Norris streets.

Two victims said a few friends who are non-Temple students let the suspects inside, where they demanded one of the students to unlock and hand over the contents of a lock box. They then pistol-whipped and punched that student, leaving him unconscious. Charlie Leone said the attack was not random, and that the suspects targeted the student that was knocked unconscious.

Chris Wildermuth (left) and Ian McLaughlin sit outside their home on North 18th Street, just off of Temple's campus. Their house was broken into and they were robbed in a home invasion that took place on Oct. 19, 2014.

After the suspects left the property, the tied-up students were freed by roommates who had remained hidden upstairs during the incident and said they immediately called 911. Both Temple and Philadelphia police responded to the incident.

Leone said police have identified each of the three suspects, and currently have two of them in custody – one of which is a juvenile. An outstanding warrant is out for a third suspect, but no arrest has been made.

A TU Alert message was sent to Temple students after the incident, just before 9 p.m.

“I think a lot of the follow-up stuff that [Temple police] did was very good,” sophomore social psychology major Chris Wildermuth, one of the victims, said. “They were very detailed, very nice and very helpful about the situation. They kept us updated about things that were happening with the case, court information, stuff that we would want to know.”

Wildermuth said he had symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder directly following the incident, including “cold sweats in the middle of the night and bad nightmares.” He no longer lives in the apartment, and he said he started commuting from his parents’ home in November for the rest of the fall semester before moving back to another off-campus residence.

“[The incident] didn’t affect my activity or anything, but it makes me more aware of the people around me, more suspicious,” he said.

Sophomore printmaking major Ian McLaughlin, another victim, said a new, negative outlook toward Temple’s surrounding area that he picked up directly following the incident wore off after a few weeks. The experience, he said, did leave him in a state of vigilance that still lingers.

“It’s more just paranoia and suspicion,” McLaughlin said. “You don’t know what someone’s planning. Walking down the street, you think about it.”

Students aren’t the only ones who have been forced to think about their surroundings. Safety concerns were heightened in October 2013 on Main Campus, after an 81-year-old professor was robbed and assaulted inside of his office in Anderson Hall. The perpetrator found a way up to the second floor, despite AlliedBarton officers stationed at the main entrance who require entrants to show an Owl Card to gain access to areas past the lobby.

Darryl Moon, 46, of the 3000 block of North Sydenham Street, pleaded guilty to charges of aggravated assault and robbery in a hearing in June 2014. He received his sentence later that year: 17-35 years in prison.

According to court documents, Moon entered Anderson around 11:30 a.m. on Oct. 29, 2013 and went up to the Intellectual Heritage offices on the second floor. He punched the victim in the face, demanding his wallet before putting a knife to the professor’s throat, according to a post on the Philadelphia Police website. After obtaining the wallet, Moon hit the victim again.

A security camera caught Moon, who is not affiliated with Temple, leaving Anderson through the second floor mezzanine doors, which police said were sealed off last summer to improve security.

Though for some students, safety concerns often dominate the discourse on community relations, others are also concerned about the families and longtime residents in the surrounding neighborhood.

Verishia Coaxum, a senior, said when she was growing up, children in the Cecil B. Moore neighborhood were expected to pursue cosmetology school or enter the military. It’s a mindset she still sees in the community she’s known her whole life. Coaxum isn’t just a student-resident of North Philadelphia; she’s a lifelong resident who grew up at 22nd Street and Cecil B. Moore Avenue. She recalls years during her childhood when students wouldn’t go past 18th Street, but now she even sees student housing between 19th and 20th streets.

Verishia Coaxum (middle) sits with her family in their home near 22nd Street and Cecil B. Moore Avenue. Verishia's mother has lived on the same street her entire life.

“Freshman year, I used to be very defensive and protective of my neighborhood, because students would say comments like, ‘Oh we don’t feel safe going past 19th Street,’ and I would get defensive because I lived at 22nd,” she said. “They would say, ‘Oh well do you feel safe there? How do you get home?’ And I was like ‘I walk.’ And then I got ‘How’s the housing?’ and I was like ‘It’s my actual house, I grew up here.’ And then the awkward silence came.”

Students like Mallon opt to rent in housing marketed to students that has sprung up on 18th Street and beyond. But Coaxum said now that she’s been a student for four years, she’s sympathetic to students’ concerns, as well. Instead of getting frustrated with their misconceptions about her neighborhood, she tries to communicate ways students and local residents can connect and begin to dispel negativity between the university community and surrounding area.

Coaxum’s family owned three properties on the 22nd Street block and still owns two today. From a young age, her mother made it clear that the question wasn’t whether or not she would go to college, but which college she would go to. When Coaxum was awarded the 20/20 Scholarship from Temple four years ago, the question of where was answered.

The scholarship, awarded to high school students living in select zip codes that are in the community surrounding the university, is based on academic achievement and requires students to maintain a 3.0 GPA. Coaxum, an English major with a distinction in poetry and criminal justice minor, looks back on four years of working closely with programs based on community relations and serving the local residents acclimating to the gradual spread of Temple’s reach.

“I think the community lacks a voice, and I think there is a disconnect between the 22nd District and the community,” Coaxum said. “That’s where I think that communication needs to be built with meetings where the police come, the Temple Police come, residents, students – its an open forum for that dialog to take place. I think at this point there lacks any specific communication. And that’s what will address a lot of people’s concerns, talking about the issue and what they have problems with.”

In her own efforts to improve that communication, Coaxum has done volunteer work through the Office of Community Relations and Women’s Christian Alliance, where much of her efforts have been working with youth – making sure they are aware of their options beyond the military and cosmetology school.

Erica Ferraiolo, a senior speech therapy major, is the president of Temple University Community Service Association. She’s been involved in the organization since close to her start at Temple, when she simply attended the organization’s events as a volunteer. TUCSA works with the Office of Community Relations to connect with local organizations and send student-volunteers to community events.

“I could see how [community residents] would get mad – they were here first, this is their territory, kind of,” Ferraiolo said. “And college kids aren’t the quietest bunch, they can be rowdy. But if there was any way we could potentially get along, that would be great. It would have to come from both sides. The college kids being more aware of their neighbors, and vice versa.”

“As a student, on campus I feel safe. … As a resident, you know sometimes I feel like Temple doesn’t care if I’m safe getting home, or just about the residents’ (safety), because it stops at a certain point.” Verishia Coaxum, senior

For Ferraiolo, volunteering within the community has been a formative aspect of her undergraduate years. Working at local service organizations has given her “a sense of what’s going on in the community,” she said.

Andrea Swan, director of Community and Neighborhood Affairs at the Office of Community Relations, believes students like Coaxum and Ferraiolo are the critical factor in bridging the gap between the university and local community. She acts as the liaison between TUCSA and community organization leaders, helping the students involved connect with local leaders and send volunteers to staff events. Since many students grew up in suburban and rural areas, Swan said, they often aren’t familiar with urban living. This can lead to an increase of quality of life complaints received by the Office of Community Relations from both students and residents, she said.

Students like Mallon – who, unlike Coaxum and other students from the area, grew up outside of Philadelphia in a non-urban area – may be informed of all the safety precautions they need to take, but do not fully understand the realities of living in a large city, Swan said. Coaxum said she does feel that the expanding presence of Temple Police is creating an overall safer environment, but she also sees the situation from a long-time resident’s perspective. The obvious distinction between Temple Police-patrolled area can make non-student residents feel like there is “separation.”

“I think that when [Temple Police] do the walks, and the patrols, that’s been helpful. It helps eliminate some of the crime,” Coaxum said. “As a student, on campus I feel safe. … As a resident, you know sometimes I feel like Temple doesn’t care if I’m safe getting home, or just about the residents’ [safety], because it stops at a certain point.”

It comes back to the disconnect between the university and community, she said. When the border first expanded, she thought the police “were looking for someone specifically” and was confused by their presence. Many residents don’t realize they can talk to the Temple Police about issues or concerns, but Coaxum thinks this could be improved “if [the police border] didn’t stop so abruptly, if it just kind of glided into it like a gradual transition.” Just like housing, she thinks police protection should be visibly equal to an observer.

BRIDGING THE GAP

Every morning just before sunrise, Fred Tookes opens the gate to his church.

Tookes is the pastor of the The Original Apostolic Faith Church of the Lord Jesus Christ, at 1512 N. Broad St. on the south edge of Main Campus.

Hardly any students step foot inside the historic church, Tookes said. In fact, he said students who stroll by the building throughout the day, including at 6 a.m. when he opens the iron gates of the church building, don’t acknowledge him.

Tookes is one of many in the community whose lives have been affected – for better or for worse – by the increase in students living on or around Main Campus. Perhaps the most visual sign of this residential growth lies in Morgan Hall, the 27-story high-rise dormitory structure that opened its doors for the Fall 2013 semester on the southern edge of campus – a building whose Temple “T” logo is visible far past Temple’s boundaries down Broad Street.

Last fall, a petition for Google to change the name “Temple Town” on Google Maps to the Cecil B. Moore Community garnered support from many, including the university. The search engine later dropped the “Temple Town” name from its maps.

Temple students’ place in the community has caused tension between them and the non-university related neighbors who surround them, as highlighted by instances like the “Temple Town” controversy. The challenges that arise from this tension are part of what Temple Police and the Philadelphia Police Department’s 22nd District are often forced to deal with.

“Temple University is North Philadelphia,” said 22nd District Captain Robert Glenn, “and North Philadelphia is Temple University.”

By midnight during a ride-along with Temple Police earlier this semester, noise complaints began rolling in. The first was cleared after responding officers reported finding hundreds of students jammed into three floors of an off-campus house on the 1800 block of 18th Street.

Undeterred, partygoers apparently turned the corner and went into another party on the next street over – the 1800 block of Bouvier Street – which was called in 10 minutes later.

“It’s a happening school,” said Lieutenant Russell Moody, who throughout two separate ride-alongs with Temple News reporters expressed a positive attitude about growth of off-campus living, which has recently coincided a growth in Temple Police’s patrol boundary this past fall.

Later during the second ride-along, students were seen knocking down a stop sign off Main Campus.

“You have students who may not be familiar with urban living,” Glenn said. “You have to co-exist with the people who live here. When you come to school at Temple and live in the Temple area, you become part of Philadelphia. I tell students, ‘Treat this area like you would your home.’”

“There are challenges,” he added. “We have to make sure those challenges are met.”

Tookes said that to combat existing tension in the neighborhood, there needs to be more interaction – not just between students and the community, but between the community and Temple’s police force.

He suggested police officers in the area should be more “involved with the community” to prevent crime, instead of “congregating” on street corners. In order to stop suspicious activity in the community, Tookes said police officers should get to know residents by name.

“Most [community members], if we were telling the truth, would say that they are for the students,” Tookes added. “We want some presence as well. It would be nice if a police officer would pull up and say, ‘Hey Brother Fred, how are you, how are you doing?’”

Tookes said he notices a lack of police presence specifically inside local businesses in both North Philadelphia and his own neighborhood of Yorktown.

“We in the community, we don’t see [the police],” Tookes said. “They don’t stop by here. They don’t stop by businesses. They don’t stop by African-American communities. … Be fair to everybody. Give everybody a fair shake.”

But Andrea Swan, who is a lifelong Philadelphian, disagrees. She said she believes there are “very strong, positive relationships” between community organizations and Temple’s police force.

“Most of the complaints we receive, if there are complaints from our neighbors, they may pertain to parking issues or off-campus student-housing issues,” Swan said. “We meet on a pretty routine basis with residential and rental associations that border our campus, and the leaders of these organizations know really well how to reach out to these individuals and campus safety.”

Gregory Bonaparte, a member and trustee of Berean Presbyterian Church located on Broad Street and a Temple mechanic, said that when he lived at 15th and Diamond streets in 1969, he rarely saw students venture past Diamond Street. Now the dynamic has changed, he said, posing new challenges.

“Eighteen- to 25-[year-olds], young folks, of any kind of race, they don’t have the same kind of respect toward older people as they should,” Bonaparte said. “Older people say, ‘I don’t want to hear no parties, I don’t want to see no drinking’ – it’s a generation gap.”

Though Bonaparte said he sees a sizable portion of students interested in becoming more invested in the community, there is still more that students can and should be doing to improve the relationship, especially in terms of crime, he said.

“Crime doesn’t have a culture, it doesn’t have a color,” Bonaparte said. “I don’t think [students] feel fear, it’s just that certain times you’re on the wrong block and the wrong people get their hands on things, and they are in the wrong place at the wrong time. Crimes that do happen on students in the community are probably because they’re doing things they shouldn’t do, not all the time, but some of the time.”

Both Bonaparte and Swan said they are aware of the negative stigma that Temple carries because of its location. Like Tookes, Swan said she hopes tension can be eased through increased interaction.

Andrea Seiss is the senior associate dean of students and co-chairs the Good Neighbor Initiative. The program, which started in 2011, stems from the university’s Good Neighbor Policy, which advocates and arranges community service projects and works to increase dialogue between students and their neighbors.

Seiss said as Temple has transitioned from a commuter to a largely-residential campus, tension between the university and the community has become more prevalent.

She added that students who started the initiative sensed frustration from community members and wanted to implement a program that would not just be about policies or rules for students and residents, but a “cultural change.”

Captain Jeffrey Chapman, in his 29th year with Temple’s police department, said it’s often difficult for students to build relationships with their neighbors when there is such frequent turnover. One method to fix that problem, he added, could be to better prepare and inform underclassmen in residence halls of effective ways in which they can build relationships with their neighbors.

Tookes said he’s not familiar with the Good Neighbor Initiative, but Seiss said she has experienced a back-and-forth exchange with community members.

“We were hearing two different things – we were hearing students saying that there were safety issues, but we were also hearing students say, ‘I do want to get to know my neighbor,’” Seiss said. “Then we were hearing neighbors say, ‘Well, our impression of Temple students is really that they’re disruptive and they just don’t care about us.’”

‘Center City North’

There’s a joke around Temple’s police station that whenever someone doesn’t know what to do when a call comes through, the call will be transferred directly to Eileen Bradley.

“That’s why I always keep my phone with me,” she says.

Bradley is engraved in the university community. She has grown with it and become a part of it throughout her decades-long career. She plans events like an annual 5K run, meets weekly with representatives from Temple’s Student Government and oversees many university-wide initiatives aimed to boost campus safety and community relations. Many would say Bradley personifies the best of what the university’s police department has to offer.

Enlarge

Someday, she said, she would like to open up a gym for low-income women. For now, though, she is still very much focused on the present.

“I can sit up here with graphs and say ‘Crime’s gone down,’ but you can say, ‘Well, I don’t feel that,’” Bradley said. “So it’s my job to make you feel safe.”

That job is not always an easy one, as the perception of safety varies for many throughout the university community.

Evan Mallon is seeking counseling through Temple’s Wellness Resource Center after realizing his behavior was drastically affecting his day-to-day life. After being mugged earlier this semester, he began exhibiting signs of post-traumatic stress disorder.

He said he has tried not to think of himself as a target, but a part of a community in need of revitalization. While he said police responded quickly and fairly, there’s a problem with the interaction, or lack thereof, on the streets.

“I don’t know that there’s anything Temple can do,” Mallon said. “I have a feeling it’s more of an economic problem in the area that needs to be solved. … If there was more of a reason to be out on those streets – other than walking to and from campus – having more eyes on the streets would encourage a safer environment.”

“If there was more business distribution in North Philadelphia, which sounds crazy because it’s such an odd area to develop, I feel like that’s the only thing,” he added. “… I don’t think the solution is more police.”

Bradley, Charlie Leone and Jeffrey Chapman of Temple Police, along with Captain Robert Glenn and Lieutenant Dennis Gallagher of the 22nd District all agree Temple is safe. The relationship between Philadelphia police and Temple is strong – the school has the largest university police force in the country and many programs designed to strengthen student safety – adding to the “layers of protection” that Leone speaks so fondly of.

Still, some like Bradley say more could be done.

In the future, she sees weekly meetings between students and neighbors, more equipment like bikes and police cars, orientations with the community or working toward getting the funding to get three community police officers on every shift.

Rumors continue to swirl regarding a football stadium to be built on or near Main Campus – a structure that, officers say, has the potential to dramatically change the area. While there would be challenges – Chapman named parking and traffic as one of the biggest hurdles – such a facility could create more jobs and also provide a space for use by members of the community, potentially creating a gateway for the university to improve its relationship with surrounding residents.

Glenn and Gallagher said a football stadium on Main Campus is something that could “create a sense of ownership for the students,” and added that such a venue could be for the better.

More importantly, it could transform the area into what Gallagher called “Center City North,” an evolution of the area that would undoubtedly change the historic Cecil B. Moore community.

Until then, the biggest concern among all officers has been unanimous: safety.

“The perception from students is that we’re only out there to stop them from drinking and the neighbors think we’re only out there to protect the students and we don’t care about the neighbors,” Leone said. “So, that’s what we’ve been doing changing that mindset. What I tell students is that we’re doing both. We want to keep you safe, that’s number one, but we also want you to be a good neighbor and we also don’t want you to put yourself at risk.”