On Dec. 1, the Philadelphia Medical Examiner’s Office received reports of 12 deaths caused by unintentional overdoses — the most ever recorded in one day in the city.

The overdoses were clustered in North Philadelphia and Kensington, according to Philadelphia’s public health department.

Over the next few days, the city saw more deaths. From Dec. 1-5, 35 people died from opioid overdoses.

The fatalities weren’t isolated incidents. In 2016, more than 700 people died from opioid overdoses in Philadelphia — about two and a half times more than the number of homicides in the city last year.

Opioids — a group of drugs that includes oxycodone, heroin and morphine — act on the nervous system to relieve pain. But they can also be overprescribed to patients or sold illegally, contributing to a national problem that Mayor Jim Kenney addressed by establishing a task force on the issue last month.

Through medical guidelines, educational programs and community effort, Temple University Hospital and the North Philadelphia community are responding to the opioid epidemic.

Community organizations, near this cluster of incidents, offer holistic care through programs focused on physical, mental and emotional health. TUH has been combating the issue of opioid overprescription since 2013, along with the Lewis Katz School of Medicine.

Opioids in the Emergency Room

Earlier this month, one of Dr. Daniel del Portal’s patients sat where his addiction to opioids began: an emergency room. The patient, who was prescribed opioids as a painkiller, had overdosed on heroin and landed in del Portal’s care at TUH.

“That’s a story we hear on a daily basis in the emergency room,” said del Portal, an emergency care physician at TUH and an emergency medicine professor. “It’s really unfortunate. We have to be really careful about what we prescribe to relieve patients’ pain.”

More than 1,000 people nationwide are treated in emergency rooms every day for the misuse of prescription opioids, and one in four people who are prescribed the drugs for non-cancer pain struggle with addiction, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the nation’s health protection agency.

Pain is subjective, which del Portal said makes it difficult to treat. He added that some patients may come into the hospital expecting an opioid prescription because they’ve heard it’s the most effective way to relieve pain.

When del Portal treats emergency room patients addicted to opioids, his personal role in combating the opioid epidemic becomes more real.

“The havoc that drugs like heroin wreak on patients is awful, and it’s not like anything else,” del Portal said. “Emergency medicine is fast-paced. We see many patients in rapid succession … but it puts it into perspective for you the risks of those [opioid] medications and whether that risk is appropriate.”

Emergency room doctor Daniel del Portal said he administers naloxone, the antidote for an opioid overdose, at least once a shift at Temple University Hospital. Here, del Portal stands in a vacant trauma bay discussing his day-to-day work. GENEVA HEFFERNAN | ASST. PHOTO EDITOR

In April 2013, to prevent overprescription, TUH released a pain treatment guideline for emergency room doctors that details the do’s and don’ts of prescribing opioids. According to the document, conditions like dental care or migraines can be treated with something besides an opioid, like an anti-inflammatory medication.

Del Portal served as the principal investigator for a study about the guideline’s effectiveness in December 2015. He and a team of three other emergency medicine physicians found the guideline had “immediate and sustained impact” on the decrease in opioid prescription for dental, neck, back and chronic non-cancer pain conditions.

All of the physicians surveyed for the study voluntarily implemented the guideline, and 97 percent said it helped them talk to patients about the possible consequences of opioid prescriptions, according to the study.

Del Portal keeps printed copies of the guideline in his jacket when he makes his rounds in the emergency room. He said discussing the guidelines with patients is worth “spending an extra few moments on.”

“Certainly it’s faster to write a script for the strongest thing you have and have the patient go home happy that they got the strongest thing,” del Portal said. “But [it’s] not necessarily the right thing for the patient, and they may not even understand the risk that it is involved with that decision that was just made.”

Physicians for Responsible Opioid Prescribing is an organization dedicated to reducing the prescription of opioids through education and advocacy for legislation. Dr. Andrew Kolodny, who received his medical degree from the Lewis Katz School of Medicine in 1999, is the group’s co-founder and executive director.

Kolodny said he worked with patients addicted to opioids for the first time as a medical student at the Lewis Katz School of Medicine in a neighborhood “devastated by drugs.” Physicians’ awareness is essential to combat the epidemic, he added.

“Whether it’s in an emergency room or an outpatient clinic, we need to stop exposing patients to opioids when it’s unnecessary,” Kolodny said.

Dr. Joseph D'Orazio (left), joined Dr. del Portal and said he prescribes opioids less than once a shift. GENEVA HEFFERNAN | ASST. PHOTO EDITOR

Dr. Joseph D’Orazio is an emergency medicine professor at the medical school, a medical toxicologist at TUH and a member of Kenney’s opioid task force. He said methods like TUH’s guideline is a step in the right direction, but there needs to be more done to limit the prescribing of opioids.

He said patients who are addicted are often treated at TUH for an issue caused by addiction, like an infection stemmed from intravenous drugs. Doctors need to focus on addiction more directly and not as a “secondary diagnosis,” D’Orazio said.

Before patients are given prescriptions, D’Orazio said they should be screened to see if they are predisposed to addiction, which can be determined by factors like genetics or past traumatic experiences.

He hopes to implement an “opioid use disorder service” at TUH that would provide inpatient treatment to patients with addiction and help them transition to outpatient services once they’re discharged. It would be a collaboration between himself, a psychiatrist, a social worker and a pain specialist.

“Temple is at the center of Philadelphia’s opioid epidemic,” D’Orazio said. “We need to be at the forefront of this problem.”

Educating about addiction

Growing up, Scott Rawls was fascinated by cigarettes.

It wasn’t a rebellious urge to smoke or the bitter scent tobacco gives off when burned that attracted him. He was curious about why his dad couldn’t stop lighting up.

“This was a guy who fought in the Korean War, a tough guy,” said Rawls, a pharmacology professor. “But he could not kick the nicotine habit.”

His father eventually died of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, a lung disease better known as COPD that can be caused by cigarette smoke.

Rawls’ childhood interest in his father’s addictive tendencies developed into his studies as a medical professional.

Now, he works in the Center for Substance Abuse Research, which is based out of the medical school and studies the biological causes and effects of addiction. The center sponsors research and educational programs about addiction, and it is composed of 30 faculty members from 11 departments in the schools of medicine and pharmacy and the College of Liberal Arts.

When he goes to Harrisburg on Wednesday, President Richard Englert will ask the state government for $5 million to fund opioid research at CSAR.

The center’s education programs target graduate students and postdoctoral fellows.

Two years ago, Rawls created the Science Education Against Drug Abuse Partnership to educate a younger demographic: students in sixth-through-12th-grade classrooms across the country. The programming teaches students about the biological roots of addiction, and recently received a $1 million grant from the National Institute on Drug Abuse.

As part of the program’s curriculum, planarians — a type of worm — are given drugs like caffeine in the lab so students can see the effects of withdrawal, relapse and tolerance. Rawls, a former high school teacher, said the use of live animals is engaging and sets his program apart from other drug education programs like Drug Abuse Resistance Education, a police-led national effort discouraging illegal drug use.

Rawls said SEADAP is increasing students’ knowledge about the science of addiction.

The curriculum is practiced in more than 100 classrooms across the country, including two at Central High School, on Olney Avenue near Broad Street. Van Truong and Michelle Thornton, two science teachers at the high school, were trained in the program’s curriculum this summer, and will begin teaching it next month.

Thornton said students from the high school will present information gathered during SEADAP’s experiments at Temple in April.

Posters — including one with the inflated head of rapper Rick Ross on a tiny body above the words “Chem Boss” — line the walls of Truong’s classroom. She said she hangs them to help the students connect science to their everyday lives, keeping them “invested” in their education.

GRACE SHALLOW | THE TEMPLE NEWS

Thornton said SEADAP helps inform students about everyday decisions they make, like choosing whether or not to drink caffeine in the morning. She added that she notices students streaming through the school’s front doors with a Red Bull energy drink or coffee every day.

Many of the students in the school’s chemistry and pharmacology classes hope to work in health care, Thornton said.

“They can go home and tell their parents about it, tell their friends about it,” Thornton said. “It’s ownership, and they feel that they have actually done something meaningful.”

Rawls also teaches the Pharmacology of Drugs of Abuse course at Temple’s medical school, which is taken by graduate students, medical students and psychology students. It studies addiction from a biomedical standpoint by talking about the neurological pathways affected by the disease and relating it to different classes of drugs, like opioids.

Steven Simmons, a third-year biomedical sciences doctoral student, has researched addiction for seven years. He said his work with Rawls as a part of the Center for Substance Abuse Research helped him understand addiction more holistically. He added that a passionate role model, like Rawls, encourages a student to keep pursuing work in the field.

“Understanding … and appreciating that can lead to some terrific introspection and discovery,” Simmons said.

Rawls’ educational and research efforts are all based on one core idea: addiction is a disease, not a moral failure.

He said if the neurons and cells of your brain are the pixels on a TV screen, addiction scrambles them up and turns them into a staticky channel without cable. He hopes his program can “unscramble” those cells.

Treatment for the Community

On Tiffany Joseph’s ankle, the name “Kathy” is tattooed in a scraggly, handwritten font.

Joseph tattooed herself in honor of her best friend, Kathy — who was like a sister to her — after she watched her die of a heroin overdose. Joseph also used heroin for more than 12 years.

“That’s how powerful the drug is,” Joseph said. “I couldn’t stop even after I saw that it took someone I loved away.”

Now, Joseph is more than two months sober.

Joseph is a patient at Pathways to Housing PA, a center in the city’s Logan neighborhood that provides housing, mental-health counseling and other services for the homeless and people with addiction.

Pathways is one of six centers in Philadelphia to receive a Centers of Excellence grant from Pennsylvania as part of an initiative by Gov. Tom Wolf. The centers encourage addiction treatment based on behavioral health, primary care and medication-assisted services.

The Stephen Klein Wellness Center on Cecil B. Moore Avenue near 22nd Street also received this grant, in addition to the Wedge Recovery Center on Broad Street near Venango, about a block from the Lewis Katz School of Medicine.

All of the centers will administer the drug buprenorphine, known under the brand name Suboxone, which is prescribed to lessen opioid dependence.

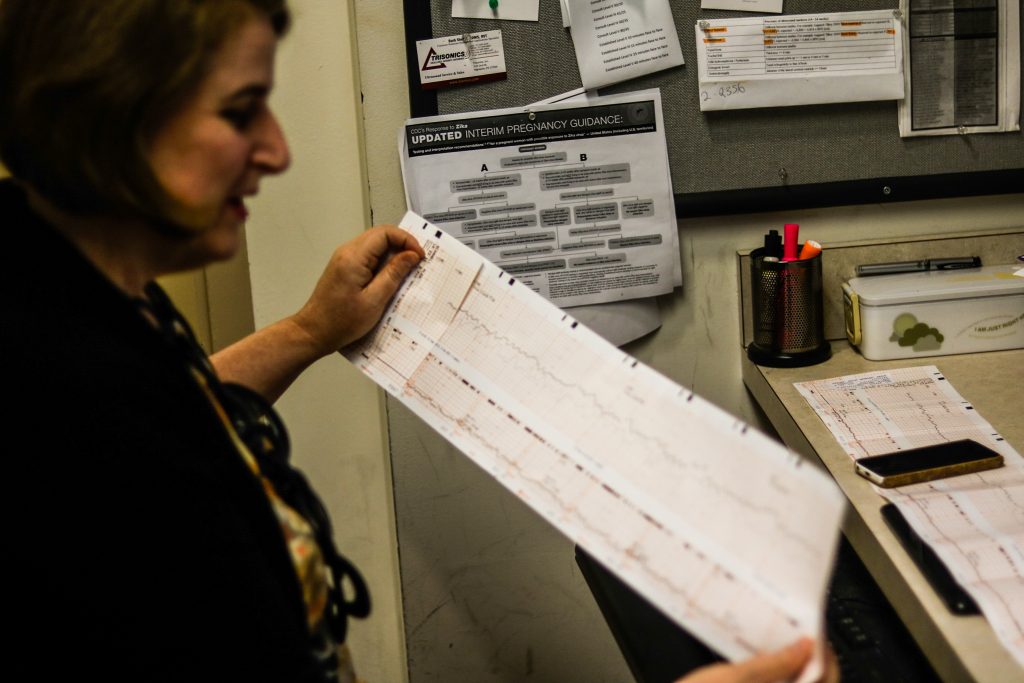

Dr. Laura Goetzl and Dr. Mary Morrison, two professors at the medical school, will collaborate with Wedge to offer treatment specifically for pregnant mothers addicted to opioids. In addition to medication, Morrison will provide mental health screenings for patients.

Morrison said addiction is often coupled with mental health disorders, like anxiety or depression, and proper psychiatric evaluations can help a patient remain on a path toward treatment.

Goetzl, who will act as Wedge’s primary obstetrician, said medication-assisted treatment is not often offered to pregnant women out of fear that treatment will harm the fetus. But refusing to treat pregnant women neglects the patients who need it the most, she said.

“Advocating for pregnant women is a justice issue,” Goetzl added. “Pregnant women don’t have the types of services available to them that non-pregnant women do. … It’s always frustrating and feels predatory.”

The center hopes to treat 300 patients a year.

Dr. Laura Goetzl looks at a fetal heartbeat in the Maternal-Fetal Center at TUH earlier this month. KAIT MOORE FOR THE TEMPLE NEWS

Other centers in North Philadelphia, however, offer even more services to combat opioid addiction. At the Klein center, there’s access to legal guidance, stress reduction programs and behavioral health services. At Pathways, it’s a “housing-first model,” meaning patients are provided a place to stay in combination with treatment. On Broad Street near Huntingdon, the organization Sobriety Through Out Patient offers counseling for mental health issues and addiction, alongside programs like music and art therapy.

Vince Faust is the wellness coordinator at STOP, but he also works with clients as a therapist and emergency worker. He said every aspect of a patient’s life is important when treating addiction — right down to what they’re wearing.

He sends clients to The Thrifty Irishman, a thrift shop in Port Richmond, when they need new clothes. If they show the store’s owner, Rob McCormack, or any of his employees Faust’s business card, they get free clothes, shoes and blankets.

“Look good, feel good,” Faust said. “If you don’t treat the whole person holistically, you can’t treat addiction.”

The centers all hope to collaborate more in the future and refer patients to one another.

Tiffany Joseph holds her first chip from Narcotics Anonymous. She receives Suboxone from the pharmacy at the Stephen Klein Wellness Center on Cecil B. Moore Avenue near 22nd Street. BRIANNA SPAUSE | PHOTO EDITOR

At the height of her addiction, Joseph said she would be on a train to Kensington to find heroin by 9 a.m. every morning, unsure if she would leave the neighborhood alive or dead.

Earlier this month, though, at 9 a.m., Joseph clutched her purse with a neon orange chip clipped to it. It’s imprinted with the emblem of the recovery group Narcotics Anonymous. She sat across the table from her doctor Lara Weinstein and Matt Tice, the director of clinical services at Pathways, who helped her find safe, sober housing. She talked about her future.

Joseph said she hopes to wake up tomorrow. She hopes to call her son, who she has not spoken to in four years, soon. Moving forward, she hopes for nothing but the best.

“All I have to say, honestly, is that I’m so grateful for everything that’s happened,” she added, crying. “I got a new life. I don’t ever want to go back to being that person.”

Grace Shallow can be reached at grace.shallow@temple.edu or on Twitter @grace_shallow.

Photos by Brianna Spause, Geneva Heffernan, Kait Moore and Grace Shallow.

Video by Abbie Lee.

Graphics by Sasha Lasakow.

Produced and designed by Donna Fanelle and Grace Shallow.

CORRECTION: An earlier photo caption misstated the nature of a typical hospital shift for Dr. Daniel del Portal. He administers naloxone, the antidote for an opioid overdose, at least once per shift.