The meeting was scheduled for a May 2013 morning in a plain office building above a Wendy’s on North Broad Street. The conference room on the fourth floor has a long table, white walls and black rolling chairs, all emblazoned with the Temple “T” logo.

Outside the room, frames line the hallway of the university’s athletic offices, celebrating Temple’s century-old sports tradition.

This would be the place, the students decided, they would tell their story.

The plan was set days before at a team meeting at the off-campus track & field house. Runners and field athletes alike compiled a list of grievances they had with the track & field program, largely including complaints that dated back years against head coach Eric Mobley, who led both the men’s and women’s teams.

Dozens would go to the office building at 1700 N. Broad St. to voice their concerns to Senior Associate Athletic Director Kristen Foley, the department’s track & field administrator. They would go as a team, because some were afraid of the consequences of speaking out against Mobley individually.

After all, students knew that Mobley had previously reprimanded athletes after they complained about the program, including revoking their scholarship or kicking them off the team. And students knew of cases where Mobley had abused them or their teammates. But most athletes held their tongues for years, and by last spring, many of them had had enough.

So when the day came to address the issues with Foley, the stakes to some of the student-athletes were clear: They were there to get their coach fired.

However, Mobley continued to run the team for more than a year after the meeting, despite the claims heard that day by Foley and at least two other cases where track & field athletes made her aware of severe team issues.

A seven-month Temple News investigation uncovered the extent of the mistreatment and neglect. Interviews with 25 people involved with the track & field teams, including current and former students, coaches and family members – along with a review of more than two dozen pages of emails, medical and legal documents – found a years-long pattern of abuse in the men’s and women’s track & field program that has led to the physical and mental deterioration of several student-athletes.

The investigation found:

- Mobley, 43, who coached from 2008 until this past June, is accused of verbal abuse, intimidation and dereliction of his coaching duties, among a myriad of other questionable and unethical practices, according to interviews with more than a dozen current or former track & field athletes.

- The track & field teams held practices without proper safety equipment, leading to at least one serious injury. A star runner was accidentally struck in the back by a flying discus during a practice in 2012, ending her career.

- A student claims she was sexually harassed by one of her coaches. She says she reported the abuse to Mobley and was told to “handle your business.” According to interviews, there is no evidence that the claim was investigated by the university, which would be in violation of federal law.

- Two students who competed under Mobley told The Temple News they considered suicide because of stress caused largely by the team. In a striking case, a former standout thrower was found in her dorm room during what appeared to be a suicide attempt after Mobley singled her out on the track. Another student-athlete, who is still on the women’s track & field team, said she had suicidal thoughts and has lived with depression because of her experience.

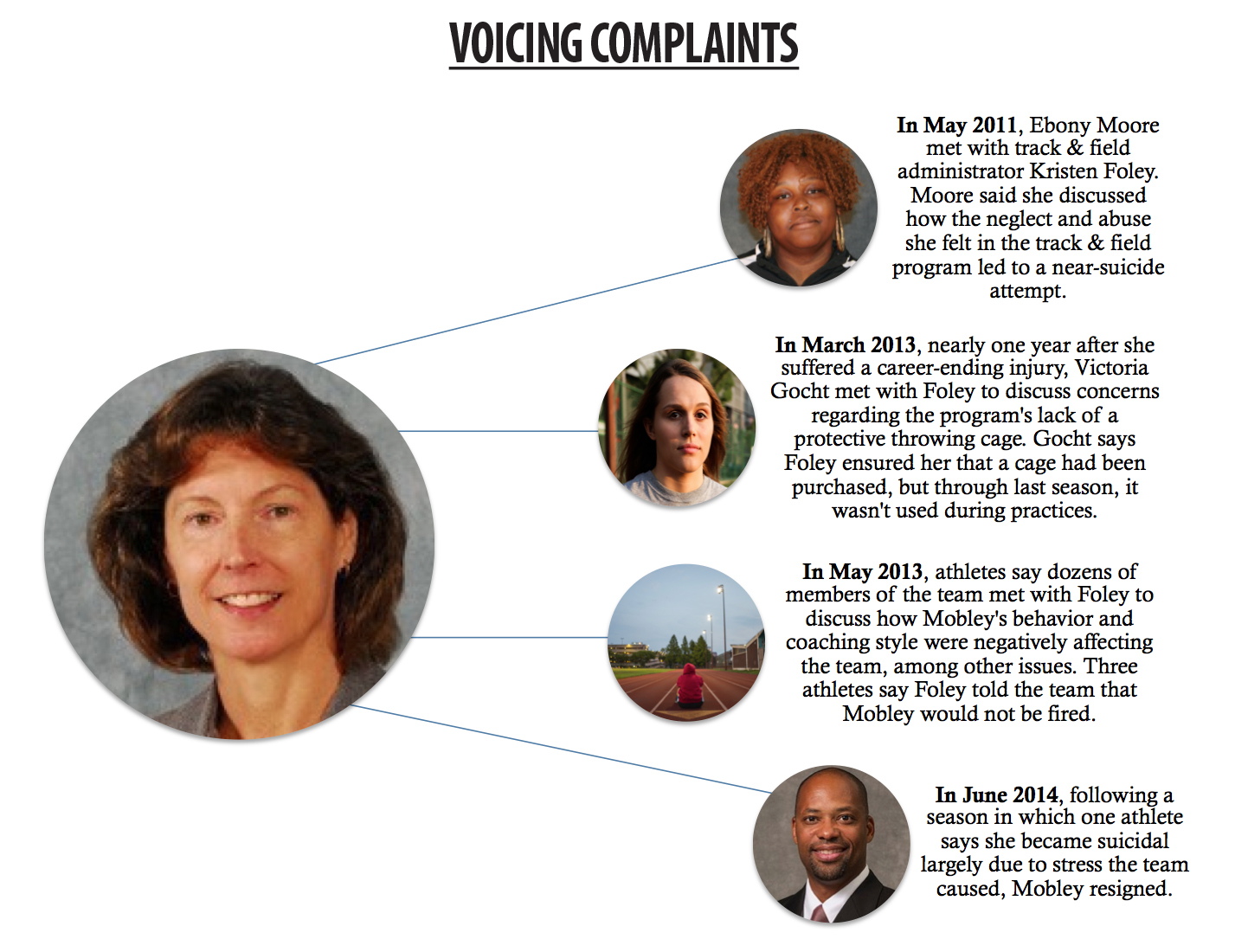

- Emails obtained by The Temple News show that Temple’s former Athletic Director Bill Bradshaw and former President Ann Weaver Hart were sent notification in 2011 of a student’s claims of abuse and sexual harassment. And at least three times since then, Foley, 50, the track & field administrator, was formally notified of the mistreatment in meetings with students, but Mobley was allowed to continue through this past season.

- Ebony Moore, who competed from 2009-11 and set a school discus record in her first season, had her scholarship revoked after complaining about the program in a meeting with Foley and Mobley in May 2011.

In June 2013, Moore filed a civil-action lawsuit against the university, Mobley and Foley, seeking $10 million in damages on claims of harassment, sexual harassment and gender-based discrimination.

A federal judge in May denied Temple’s motion to dismiss those claims, likely ensuring trial or settlement in the case. The athletic department announced Mobley’s resignation a month later.

Andrew Thayer | TTN

Repeated attempts to interview Mobley were unsuccessful. After not returning several phone calls, he emailed a reporter declining to comment, citing unspecified student privacy laws.

Mobley answered a follow-up phone call and declined to speak further, referring the reporter only to his email.

It’s unclear if President Theobald, who took office in January 2013, was notified of the abuse that students reported, but the athletic department has been scrutinized during his tenure. Athletic Director Kevin Clark conducted a yearlong review of the department last year that led to Clark recommending that the university eliminate seven of its 24 Division I sports in December, citing budget concerns.

Five of those sports were cut on July 1, including men’s track & field, but the women’s team remains.

Clark took office in November 2013 after Bradshaw, the former athletic director, retired last May. Whether Bradshaw’s exit had anything to do with the derelict track & field program, Temple won’t say. Theobald, Clark and Foley all declined to be interviewed for this article.

Reached by phone, Bradshaw declined to comment on specific cases, citing the university’s pending litigation, but said, “Any kind of information that comes in, whether it’s spoken, written, or whether it’s at a reception and someone came up to me … all of those accusations and innuendos are taken seriously and have to be.”

Hart, who is now president of the University of Arizona, declined to comment through her secretary, citing Temple’s pending lawsuit.

In August 2011, a former distance runner on the track & field team, Roswell Friend, committed suicide. In a relatively high-profile case, Friend ventured out alone for a run one Thursday evening and jumped off the Benjamin Franklin Bridge.

As part of this story, The Temple News investigated Friend’s death, but according to interviews with two of his friends and roommates, a former neighbor and multiple interviews with Friend’s mother, his suicide is believed to be unrelated to Temple track & field.

The Temple News investigation comes during a time when activists are lobbying for the rights of student-athletes in Division I athletics, as the industry becomes more financially bloated. And problems like coaching abuse and administrative scandal seem to have increasingly become part of the college sports lexicon.

There is also a growing concern here about how the administration has handled student abuse cases. In May, it was announced that Temple is one of 55 universities nationwide under investigation by the U.S. Department of Education for possible violations to Title IX requirements regarding sexual assault and harassment cases.

With Moore’s case, however, harassment was only the beginning.

A plan derailed

Ebony Moore arrived at Temple in 2009, a transplant of Missouri, Georgia and Alabama. She grew up in St. Louis in what she describes as an easygoing, liberal family.

When she was in the third grade, Moore began practicing meditation. She and her family would go into a back room in their house to sit and think. Moore recalls the sessions as times when she would focus on something she really wanted.

And soon enough, she knew what that was.

Moore began competing in track & field in ninth grade at Winder-Barrow High School in Georgia. She won the Class AAA state championship in the discus throw in 2006 and began getting looks from Division I colleges across the country.

It was only natural that Moore excelled at track & field. Her mother is in the all-time record books at Wichita State University as a shot-put thrower.

“I did it because she did it,” Moore said. “And I ended up being really good at it.”

Former thrower Ebony Moore broke a school record during her first season with the team. During her second year, she said harassment and neglect from her coaches led to a near-suicide attempt. COURTESY | Ebony Moore

She was recruited to come to Temple by the Owls’ former coach, Stefanie Scalessa, who led the men’s and women’s teams from 2004-8. Moore chose to attend Jacksonville State University in Alabama for her freshman year, but she said later she always intended to end up at Temple.

Moore had her life plan laid out. After leaving college, she hoped to compete in the Diamond League, a series of track meets hosted by the International Association of Athletics Federations. She had a timeline of marks that she wanted to make at Temple before she graduated.

But once Moore began competing here, her plan was derailed.

Moore’s story, revealed in a 14-page complaint filed in civil court last June and reiterated to The Temple News during more than three hours of interviews, details two years of bullying and harassment that Moore suffered from her coaches and teammates.

Moore said the mistreatment began soon after she and her sister joined the team in 2009. In separate interviews, the sisters said they were teased about their southern accents and harassed by their teammates.

In her civil complaint, Moore claims she experienced an “endless amount” of ridicule.

“I was called ‘fat bitch,’ ‘ghetto bitch’ and many other insulting epithets on a daily basis,” Moore wrote in an addendum to the complaint.

Other student-athletes recalled the name-calling, including members of Moore’s events group.

“She would laugh it off, but you can tell on the inside that after a while it all boils,” said Emmanuel Freeland, a former sprinter who competed from 2009-11.

“Ebony was bullied,” said Eric Brittingham, a former javelin thrower who said he experienced his own mistreatment.

In an interview, former thrower Grant West denied there was bullying. Moore was called lazy “a million times,” West said. And he stands by it.

“She would laugh it off, but you can tell on the inside that after a while it all boils.” Emmanuel Freeland

“There was no bullying,” West said. “The kids that worked hard called out the kids that didn’t work hard.”

Moore’s high school coach Isaiah Berry, however, challenged the complaint about her work ethic. Berry said Moore was always one of the first athletes at practice and one of the last to leave. He called Moore “smart,” “polite,” and a “good person.”

And Moore went on to break Temple’s all-time discus throwing record in her first season with the Owls.

“With technical events in track & field, you don’t become champion by slacking off,” Berry said. “She didn’t do that.”

Moore insists that whatever issues her teammates had with her work ethic were caused by the toxic relationship she had with one of her coaches, who Moore says tried to pursue a sexual relationship with her.

During a ride in the team van in her first season, Moore said, a student asked the coach which of the athletes they would most want to have sex with.

It would have to be Ebony, the coach said, according to Moore’s account.

Moore said the coach asked her to come up to the coach’s hotel room during the conference championship weekend in Rhode Island in February 2010. When Moore denied sexual advances, her relationship with her coach soured, she said. Moore said that by the end of her first season, the coach ignored her almost completely.

Edward Barrenechea | TTN

“I would say the best word to describe my experience on the two years I spent on the Temple track & field team is ‘inappropriate,’” Moore said. “It was just completely inappropriate.”

Moore said she reported the harassment to head coach Eric Mobley, but, according to her complaint and multiple interviews, his response was “handle your business.” Moore says Mobley repeated this response, even as the abuse she reported progressed into groping.

The Temple News was unable to corroborate Moore’s specific claims of sexual harassment with any of her former teammates. Reached by phone, the accused coach, who has since left the team, declined to comment. The coach will not be named in this story.

Still, universities are required by federal law to investigate claims of sexual harassment reported by a student. Interviews with Moore indicate there is no evidence that such a process took place at Temple in this case.

Also a victim of name-calling, Moore’s sister left the team during her first year. Moore wanted to stay.

“I thought [the second season] would go much easier than my first one, that I would be treated better, that something would change,” Moore said. Track & field was her “livelihood.”

But after returning to Georgia for the summer, she began having panic attacks during workouts. She said she was later prescribed anti-anxiety medicine.

Moore recalls telling Mobley upon returning to Temple that she was on medication. She said the coach laughed about it.

The Fallen Star

A scream pierced the air at the Temple track & field complex during an afternoon practice on March 30, 2012.

Victoria Gocht, the 2010 Atlantic 10 Conference Rookie of the Year, had collapsed to the ground near the southeast corner of the track. An athletic trainer rushed to her aid.

For at least a minute, Gocht couldn’t move her legs. She thought she was paralyzed.

Practicing nearby, the team’s throwers were among the first to realize what happened: One of them had over rotated while launching a discus, which sent it flying in the wrong direction.

It was a typical mistake for a field athlete, one that teams are supposed to account for with proper safety equipment. Division I track & field teams are required by the NCAA to utilize a protective cage for throwers during competition and are advised to use them in practice.

But Temple didn’t have a cage. A partial throwing net, sometimes set up during practice, sometimes not, wasn’t erected that day. As a result, the four-and-a-half pound projectile struck Gocht, practicing in lane three, squarely in the back.

Gocht said it was the most severe pain she’s ever experienced. She was later taken to Temple University Hospital and diagnosed with a back contusion.

Former runner Victoria Gocht suffered a career-ending injury during a practice in Spring 2012 when she was hit in the back by a flying discus. As recently as the end of this past season, the program did not utilize a protective cage for its throwers.

On the other side of the track, then-assistant coach Jeff Pflaumbaum looked on feeling devastated. It was his first year as the team’s throwing coach, but Pflaumbaum understood the implications of the program’s lack of a protective cage.

Pflaumbaum called the first days of the 2012 outdoor season the “most stressful week of coaching” he has ever experienced. After Gocht was struck by the discus, he considered resigning from the team due to fear of legal ramifications.

“With a good cage, it would have stopped that,” Pflaumbaum said of Gocht’s injury.

Before the incident, Gocht had a promising future in track & field. She won a gold medal in the 800-meter race at the 2011 A-10 outdoor championships and was named the top freshman in the conference in 2010. But her injury put her career at a halt.

“I think (Mobley) was just angry. He would say, ‘You suck,’ out of anger. I don’t think he was trying to motivate us.” Cullen Davis

Gocht is merely one of a number of student-athletes who were victims of what students describe as a grossly mismanaged track & field program. Interviews with more than a dozen members of the program indicate that students were neglected or unfairly treated by their coach, Eric Mobley, and not properly accommodated by the athletic department.

Among other practices, athletes say Mobley often singled people out in front of the rest of the team, including individual students or event groups. Athletes recalled instances in which Mobley told students they “f—ing suck.” Some also remembered the head coach separating members of the team based on performance level and belittling them.

Former distance runner Cullen Davis, who transferred to the University of Pittsburgh after his sophomore year in 2012-13, said he felt powerless and abused as a Temple athlete. He recalls a bus ride after the 2013 indoor conference championships where Mobley told students that he would have “punched you guys in the face” if he was one of their teammates.

“I think [Mobley] was just angry,” Davis said. “He would say, ‘You suck,’ out of anger. I don’t think he was trying to motivate us.”

Davis said his mental health suffered due to the mistreatment, which led to a decline in his grades.

“If you’re a track & field runner, you can second-guess yourself,” Davis said. “Does anyone really care if I achieve anything other than my parents? I felt like, at Temple, I was just worthless and nobody really cared.”

Otherwise, athletes said the team lacked coaching leadership and organization. Some students hardly ever received coaching from Mobley, who worked primarily with sprinters during practices. The team’s resources, too, were scant.

Temple ranked last by far in operating expenses among the track & field programs in its conference last year, according to data from the U.S. Department of Education. Overall in 2013, Temple had the second-smallest athletic budget in its conference, but sponsored the largest number of sports.

It was that discrepancy, along with concerns about the program’s facilities, that the administration said was the reason for the men’s track & field team’s inclusion in last December’s sports cuts.

The lack of resources from the top down materialized in ways as serious as not having a throwing cage or pole-vaulting pit to other glitches like athletes not being supplied with the proper footwear.

As a result, the low-budget team sometimes put the safety of students in jeopardy.

Eric Brittingham was a Temple thrower from 2008-11. He threw the javelin more than 60 meters at the A-10 championships in his freshman year to qualify for the NCAA regionals.

Brittingham said he suffered a torn ligament in his elbow during his sophomore year and planned to redshirt and return to competition the following season. Brittingham says Mobley pushed him to return to competition too early, and a year later he was removed from the roster because he was told that his “attitude was bringing down the team.”

“When he saw that I wasn’t producing results and he wanted me to come back – and I said I physically can’t yet, I will be ready to next year – his opinion differed from mine, which is why he kicked me off the team,” Brittingham said.

Even for athletes who achieved under Mobley, the program’s limitations were obvious.

“It interferes with my ability to do anything athletic. My life has drastically changed because of that. There’s the fact that I never got to see my potential for this … I felt like it was stolen from me.” Victoria Gocht

“If I could sum up the program in one word, it would be ‘neglect,’” said Travis Mahoney, a three-time All-American who competed from 2008-12 and is largely considered to be the top distance runner in school history.

A few days after she was struck by the discus, Gocht walked into Mobley’s office in McGonigle Hall to address her concerns about competing that weekend in the Florida Relays. Gocht sat down across from Mobley, but before she could get a word out, he spoke first.

You’re going, Mobley said, according to Gocht’s account.

Wanting to help her team, Gocht didn’t argue. Temple’s athletic trainers had cleared Gocht to compete, so days later, she boarded a plane.

Upon arriving at the track & field complex at the University of Florida, Gocht noticed something flying overhead.

Panicking, she flinched. However, the soaring figure was not a discus. It was a bird.

Gocht’s eyes moved toward the throwing cage adjacent to the track, where she was scheduled to run later that day. Suffering from what she calls “severe anxiety,” Gocht left the meet and hid behind a set of bleachers. With a piece of Kinesio tape attached to her still-healing back, Gocht stood alone, trembling and crying.

Gocht eventually returned to the track that day to compete in the women’s 800-meter run – an event in which she held the A-10 record. She finished in last place with a time of 2 minutes, 22.19 seconds – one of the worst performances of her collegiate career.

“I still have pain and it interferes with my ability to run,” Gocht said. “It interferes with my ability to do anything athletic. My life has drastically changed because of that. There’s the fact that I never got to see my potential for this … I felt like it was stolen from me.”

After the weekend, Gocht was placed on medical leave, she said, and stayed off the track for most of the next two years.

She never competed at the collegiate level again.

A CALL FOR HELP

Ebony Moore lived Temple track & field.

Every day, she woke up at 6:30 a.m. for morning lift. After about a 90-minute workout, there was a break for class and lunch, then back to the track for afternoon practice. When Moore got home at night, she did event-specific stretching in her dorm.

“Track dictated every aspect of my life,” Moore said. “My friends. My social life. The route that I took in academics. Even from what you eat to the clothes that you wear, it’s predominately dictated by your sport.”

But after a troubled first season, she said her second season was “even worse,” largely due to the neglect she felt from her events coach and her fractured relationship with head coach Eric Mobley.

On Wednesdays at 3 p.m., Mobley would run team meetings in McGonigle Hall, where students say he would often single them out or curse at the team.

“I knew somebody was going to get the ax,” Moore said. “And I used to be so scared … I would be shaking.”

To be sure, coaches of all sports at colleges across the country verbally reprimand athletes at team meetings. And high school and college coaches, including others at Temple, commonly use profanity.

But students say the yelling wasn’t coupled with the typical guidance that athletes want out of their head coach. And whether one would question the severity of the verbal abuse that students claim against Mobley, it would be difficult to dispute the effects that it had on Moore.

“I knew somebody was going to get the ax. And I used to be so scared ... I would be shaking.” Ebony Moore

Moore said Mobley’s behavior caused her to constantly live with fear. Fear of being yelled at. Fear of being singled out. Fear of not being good enough.

And the neglect Moore felt from other track & field officials, like the athletic administration and her events coach, caused further damage to her mental health, she said.

Moore said her events coach for the 2010-11 season, Aaron Ross, hardly ever worked with her. According to Moore’s complaint and multiple interviews, Ross would favor the men’s throwing team over the women’s team and she rarely received coaching from him.

“Event after event I would show up to practice and I would be treated very poorly,” Moore said about her second season. “I would do the conditioning that everyone else was asked to do, but I would get picked on and bullied.”

Moore said she attempted to notify Mobley of these and other complaints that year, but was rebuffed. And the thought of notifying an administrator seemed fruitless to Moore due to Mobley’s behavior.

After a group of Moore’s teammates attempted to contact the athletic director with a question about summer aid, according to Moore’s complaint and interviews, Mobley told students to “never contact my f—ing boss” and threatened to kick them off the team if they did so.

Edward Barrenechea | TTN

My boss is in full support of everything I do, Mobley said, according to multiple interviews with Moore.

Almost none of the former athletes interviewed said they would have felt comfortable going to Mobley with a team or personal issue.

It all came to a head at the end of Moore’s second season when, after being singled out by Mobley on the track, she finally broke down.

At practice on April 20, 2011, Moore didn’t see her name on the roster to compete that weekend for the Widener Invitational in Chester, Pa. Moore says she confronted Mobley and he “went off” on her.

“I was trying to plead my case,” Moore said. “I was like, ‘Please don’t take me off the itinerary. I’ve been trying my hardest.’ He just dismissed me and embarrassed me in front of everybody and kicked me off the track. So I left.”

Moore said she doesn’t remember much of what occurred after practice that day.

Meanwhile, hanging out on Liacouras Walk, Amber Moore was becoming worried. She had plans to meet her sister that afternoon to partake in Spring Fling activities together, but Ebony wasn’t showing.

When Amber got her sister on the phone, Ebony sounded hysterical. Amber said Ebony had grown detached and moody throughout her second season with the team, but from the way her voice sounded on the phone, Amber could tell her sister needed help.

“He f—ing hates me,” Amber recalled her sister saying. “It’s not fair.”

“I have sat in a crowd of my peers with my head down, hair covering my face and tears moistening my shirt and my coach has still overlooked me.” Ebony Moore

Amber rushed to the fifth floor of her dormitory at 1300 residence hall and knocked on her sister’s door. Ebony answered, changed from her dress at practice, red-faced with tears in her eyes.

Amber said Ebony’s dorm was a mess of clothes and other items thrown throughout the one-bedroom apartment – like a “tornado had come through.”

At the end of the mess was an open window, the screen for which was lying on the floor. Amber said she envisioned what could have happened – her twin sister, born six minutes earlier than her, had been contemplating an imminent attempt to end her life.

Amber called an ambulance and Moore was taken to a local hospital. Jeanine Moore, Ebony’s mother, took an emergency flight from Georgia to the city. She said she was informed that her daughter had been transferred to Fairmount Behavioral Health System – a hospital specializing in depression, suicidal thoughts and other mental-health problems.

The Moore family said the hospital advised that Ebony remain under its care due to her condition, but Jeanine Moore arranged for her daughter to be released to her. She says she didn’t recognize Ebony when she first saw her in the hospital.

“She didn’t even look like my kid,” Jeanine Moore said.

Four days after her hospitalization, Ebony Moore drafted a long list of grievances that described in detail the abuse she claimed to have been experiencing. Later, Moore would submit the same list as an addendum to her civil complaint.

“To cry out for help and to be ignored is perhaps the most destitute feeling to encounter while living the human experience,” Moore wrote. “I have sat in a crowd of my peers with my head down, hair covering my face and tears moistening my shirt and my coach has still overlooked me.”

“Coach Mobley is aware of how far I am from home, my mental health situation and my dearth of support. He just does not care. After two seasons of attempting to ‘handle my business’ and ‘stop bitching’ I am convinced that this is what being a Temple Owl is all about.”

WE’RE NOT GOING TO FIRE HIM

The student-athlete was skipping classes, missing assignments and flunking her finals. She had already decided her future midway through the Spring 2014 semester, and her GPA was of little importance to fulfilling it.

She was planning her suicide. The student-athlete knew when she was going to kill herself and how she was going to do it.

The student is an upperclassman on the women’s track & field team. She requested to remain anonymous to discuss sensitive issues due to the fact that she’s still on the roster.

The student said the pressure to succeed in track & field coupled with the lack of support she felt from the program significantly contributed to the decline of her mental health. As recently as the end of this past season, she said, the mistreatment contributed to her living with “major depression.”

A year ago, she sought to have the problems resolved. She went with teammates to confront Kristen Foley at the university’s athletic offices with the hope that the health of the program would improve.

Once they arrived at 1700 N. Broad St., there were too many students to fit inside the lobby’s elevator, so some took the stairs to the fourth floor. Multiple students said Foley was visibly surprised at how many had showed up. Foley led the team to a conference room down the hall and sat near the end of the table closest to the door.

Dozens of members of the 2012-13 men’s and women’s track & field roster filled the seats around her.

Foley, who previously served as the women’s basketball head coach and has worked for the university for 19 years, oversees the administration of 12 Temple sports teams, including track & field, according to her profile on the athletics website.

Enlarge

Avery Maehrer | TTN

At least three times since 2011, a member or members of the track & field teams have met with Foley to formally address issues they were having with the program. Ebony Moore met with Foley after she nearly attempted suicide in April 2011. Victoria Gocht met with Foley last year after she was hit with a discus in practice. And a group of track & field athletes gathered outside Foley’s office in May 2013.

Students said the majority of the complaints discussed during the team meeting with Foley involved Mobley’s coaching style, including verbal abuse and general mismanagement of the teams. The athletes also said how the teams’ resources, including the program’s lack of a throwing cage and pole-vaulting pit, were limiting them.

After the meeting, Foley acknowledged that some of the issues were her fault. She told the students she would address the problems.

But she also made one aspect of the team’s situation clear.

We’re not going to fire Mobley, three students recall Foley saying.

Temple hired three events coaches and promoted a volunteer to full-time assistant before the Fall 2013 season, but it’s unclear if the additions were related to student complaints.

“I felt like I wasn’t given the support I needed. I felt alone and that there was no one I could talk to.”

It wasn’t until this summer that Mobley left his position. In a brief press release on the Temple athletics website, the university announced his resignation on June 6, 2014.

“Temple Athletics thanks him for his service to the program and wishes him well in his future endeavors,” the release read, noting that Mobley was named conference coach of the year in 2010.

At best, the lack of resolution stemming from the Foley-run meetings demonstrates a failure in the athletic department to properly remediate student complaints. At worst, the meetings implicate Foley as an administrator who neglected to suppress the abuse that occurred in the program she oversaw.

Either way, the outcomes of the meetings are clear; Mobley was allowed to continue, and in each case, the problems went largely unsolved.

The student whose mental health had suffered said her experience didn’t get any better after the team met with Foley in 2013. Midway through the following season, she said, she began entering a “dark place.” She lost her appetite and began having suicidal thoughts.

“I felt like I wasn’t given the support I needed,” she said. “I felt alone and that there was no one I could talk to.”

Bradshaw, the former athletic director, said he doesn’t recall a track & field team issue other than Moore’s that “was considered serious.” In an interview, he defended Foley, but declined to discuss specific cases.

“I trust her judgment and her fairness and her honesty and her accuracy,” Bradshaw, who worked with Foley for 11 years, said. “No other administrator goes above and beyond for the welfare of athletes like Kristen Foley. If there was anything that was serious and egregious, I have confidence that she would have passed that on.”

It’s unclear if Foley notified Theobald or Clark of the complaints she heard. After an interview with the administrators was denied, a Temple spokesman said only in a statement that the university is “committed to providing a safe and supportive environment for all of our students, including our student-athletes.”

“As we became aware of student concerns in track & field, we pursued a course of action that included meeting with the students and meeting with the coaching staff,” said Ray Betzner, associate vice president for executive communications. “In addition, university staff from several offices on campus worked together to take appropriate steps in responding to these concerns.”

Just two months before dozens of athletes gathered in her office, Foley held a separate meeting with Gocht. It had been nearly a year since she suffered a career-ending injury, but Gocht scheduled her own personal meeting with Foley to discuss her discomfort in returning to practice without a protective cage.

Gocht said Foley ensured her in the meeting that a cage had been purchased and would be installed. Gocht and members of the team say they saw the cage being delivered – the throwers helped unload it from a truck.

Athletes say they were told it wasn’t installed due to a fear of community residents climbing on top of it and endangering themselves.

Both the current and former athletic director wouldn’t comment on the cage, but students say practice techniques were adjusted after the incident with Gocht. As recently as the end of this past season, the cage was not used.

“I feel like she was just trying to tell me whatever was necessary in order to satisfy me,” Gocht said of Foley. “She just told me what she thought I wanted to hear. I don’t think she actually cared. She had the meeting with me because that’s her job.”

Outgoing senior Gabe Pickett said Foley scheduled individual meetings with him and other athletes in May 2014. Pickett says he was asked about Mobley’s temperament toward the team, how the head coach handled himself and the communication between the staff and students.

The next month, Mobley was out. Elvis Forde, who coached at Illinois State University for 12 years, was hired as Mobley’s replacement last week.

The student who had been considering suicide says she eventually sought treatment at Tuttleman Counseling Services. She said her mental health is improving; she is seeing a psychologist and taking antidepressants.

She said she was going to transfer next season, but she’s returning to the track & field team now that Mobley has resigned.

“I just felt like for my own sanity I would have to leave,” she said. “Now I’m kind of hopeful about what will happen next year.”

“I’m going to give it all that I have.”

THE ENDGAME

Stop this foolishness before it goes too far, the uncle implored.

Othello Mahone, a Maryland real estate contract developer and Ebony Moore’s relative, was writing an email to President Ann Weaver Hart in May 2011. Following her stay at the Fairmount Behavioral Health System, Moore was notified that her athletic scholarship was not being renewed for the following year, Mahone’s email said.

“How do you think this will play in front of a jury?” Mahone wrote.

In a previous email to both Hart and former Athletic Director Bill Bradshaw, Mahone sought to formally notify top officials of Moore’s claims of abuse. In an attachment to Mahone’s email, under subheads titled “verbal abuse,” “intimidation,” “gender-based discrimination” and “sexual misconduct,” Moore detailed her allegations against the teammates who bullied her, a coach who harassed her and the head coach who ignored her.

Bradshaw wouldn’t say in an interview if he recalled receiving the email.

“It wouldn’t be the only email that I got from relatives of the 600 student-athletes that I had,” Bradshaw said.

Mahone received no response from Hart or Bradshaw. Instead, he scheduled a meeting with Kristen Foley, the athletic administrator of the track & field program, along with Moore, assistant coach Shameeka Marshall, throwing coach Aaron Ross and head coach Eric Mobley.

The group met on May 4, 2011, in the fourth-floor conference room of the university’s athletic offices. Moore reiterated to Foley and her coaches the issues she was having, including her near-suicide attempt, according to her account. Moore said Foley was an active participant in the meeting, asking her if she was satisfied with the team’s facilities and other accommodations.

Moore and her uncle left the meeting with the understanding that the issues were formally addressed and that both parties would attempt to have a better relationship next season, despite Mobley’s behavior at the meeting.

According to Moore’s complaint and interviews, Mobley said during the meeting that he is “not responsible for the well-being” of his student-athletes.

Did Phil Jackson have to motivate Michael Jordan? Mobley said during the meeting, according to separate interviews with Moore.

Mahone said he talked one-on-one with Foley after the meeting to discuss Moore’s future. The conversation was “positive,” Mahone said.

“I thought she was going to be more helpful,” Mahone said later. “I don’t know if she possesses the authority to be more helpful or not. What I thought was going to happen did not.”

Skyler Burkhart | TTN

Less than three weeks after the meeting, Moore received an email from Student Financial Services saying that, upon the recommendation of the athletic department, her athletic scholarship for the upcoming season was not being renewed.

Moore appealed her non-renewal and a hearing was scheduled with the university’s Financial Aid Appeal committee, which typically consists of the director of Student Financial Services and at least three other faculty members outside of the athletic department.

Moore, the committee and other officials met on July 28, 2011 at Barrack Hall. Moore was flanked by her mother, sister and uncle, but only she was allowed to speak on her behalf. Mobley and Foley were both present at the meeting, according to the Moore family.

Both sides were given a chance to present their case to the committee – the athletic department for why Moore’s scholarship was not renewed and Moore for why she found it unjust.

In its presentation, the athletic department submitted a false account of Moore’s academic status, according to Moore’s complaint and interviews with the family.

Moore rebutted by telling her story, including her near-suicide attempt. After roughly a half-hour of conversation, the family said, at least one of the committee members was in tears.

“In my opinion, I don’t think the panel was prepared to see the track & field staff was so blatantly wrong,” Moore said later.

Like before, the family said, Mobley became irate at the meeting. According to multiple interviews with Moore, one of the committee members even snapped back at Mobley.

You can’t talk to me like that; we’re not on the track, a member said.

However, the committee denied Moore’s appeal. The committee, according to the family, found Mobley and the track & field program to be at fault, but considered the relationship “too toxic” for Moore to continue.

The committee ruled to grant Moore non-athletic aid for the 2011-12 year that equaled her aid for the 2010-11 year. For Moore, this wasn’t good enough.

“I expressed: If [Mobley] is wrong, why is he allowed to coach?” Moore said. “I was told that’s not in their hands or that they couldn’t give me a definitive answer.”

The chair of the committee was John F. Morris, Temple’s former director of Student Financial Services. A letter sent to Moore that submitted the committee’s ruling in writing indicates that the other committee members at the time were Marylouise Esten, associate dean of students in the Beasley School of Law, Johanne Johnston, assistant dean for admissions and financial aid in the law school and Jeffrey Montague, assistant dean in the School of Tourism and Hospitality Management.

When interviewed, Moore couldn’t recall all of the names of the committee members, but she confirmed them after viewing the letter. Morris, Esten, Johnston and Montague all declined to be interviewed for this article, citing student privacy laws.

The committee had the power to not renew Moore’s athletic scholarship, but it’s unclear if they had any authority to take further action against the track & field program. Members wouldn’t say if they made any other formal recommendation to the athletic department regarding Moore’s case.

In an email sent through a spokesman, Sherryta Freeman, senior associate athletic director in charge of compliance and student-athlete affairs, said Temple’s appeals committee can rule on the side of the university, the student or come to an alternative decision, but Freeman declined to discuss specifics.

“If a coach recommends nonrenewal of a scholarship, he or she meets with a senior athletics department administrator to discuss the situation, and appropriate athletics staff also review the circumstances and associated documentation before a nonrenewal decision is made,” Freeman said.

It’s possible Moore could have still competed for the team that year without athletic aid, but she said she took the committee’s ruling as Temple’s final say on the matter. She didn’t feel as though she would have been welcomed back, though, despite all she had been through, she said she was still willing to compete.

“I had done nothing wrong,” Moore said. “This is my sport. My life, really.”

Bradshaw, the former athletic director, said he thought Moore’s case was “fairly adjudicated” by the committee, but declined to discuss specifics.

Moore’s lawsuit against the university, Mobley and Foley is now in the discovery phase.

“My end goal is to have people know that if somebody is doing something wrong to you, the burden shouldn’t be on you to be quiet and make that institution comfortable while you suffer,” Moore, who is representing herself in the case, said.

“When I look at my case and I go online and go through the documents, there’s always a certain button for related cases,” Moore said. “And if you click on mine there are no related cases. I’m sure people have suffered from things like this or had these things done to them and they didn’t say anything. If you look at my case, the statute of limitations is almost over, but I decided I could not let this pass and send the signal that this is OK.”

Moore completed her studies at Temple after her athletic scholarship was revoked. She received weekly counseling and said she was diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder by a Temple doctor.

Moore, living at home in Georgia, said she still needs weekly counseling, but can’t always afford the appointments. She goes twice a month if she’s lucky, she said. She continues to take daily anti-anxiety medicine.

In May 2012, Moore graduated from Temple with a degree in neuroscience. She says she wants to be a psychiatrist.

Avery Maehrer and Joey Cranney can be reached at editor@temple-news.com

Evan Cross and John Moritz contributed reporting.

Photo illustration by Kara Milstein.

Produced by Chris Montgomery and Patrick McCarthy.

Need Help?

Students, including student-athletes, who feel they are in need of mental health support can contact Tuttleman Counseling Services at 215-204-7276. The Suicide/Crisis Intervention Hotline for Philadelphia is 215-686-4420.