Content warning — This project contains graphic content that may be triggering for some readers.

On May 1, 2014, the list of 55 was released. The list is extensive, with no room for interpretation. Temple was among the original schools listed.

The U.S. Department of Education released the names of 55 universities under investigation for possible violations of federal law over the handling of sexual violence and misconduct, and Temple was one of them. The list has since grown to include 175 institutions.

The university’s inclusion on this list had to come from complaints—complaints that tipped the proverbial dominoes that would topple Temple onto the list of non-compliant schools when it came to sexual violence. Under federal law, this includes physical sexual acts perpetrated against a person’s will or where a person is incapable of giving consent. This means rape, sexual assault, sexual battery, sexual abuse and sexual coercion.

Glossary

As defined by the Clery Act’s National Incident-Based Reporting System from the Uniform Crime Reporting Program.

Sex offenses are separated into two categories: forcible and non-forcible. Forcible is defined as any sexual act directed against another person, forcibly and/or against that person’s will; or not forcibly or against the person’s will where the victim is incapable of giving consent.

There are four types of Forcible Sex Offenses:

Rape is the carnal knowledge of a person, forcibly and/or against that person’s will; or not forcibly or against the person’s will where the victim is incapable of giving consent because of his/her temporary or permanent mental or physical incapacity (or because of his/her youth). This offense includes the forcible rape of both males and females.

The definition of rape was updated in the Uniform Crime Reporting Program in 2013 by the FBI as the penetration, no matter how slight, of the vagina or anus with any body part or object, or oral penetration by a sex organ of another person, without the consent of the victim.

Forcible Sodomy is oral or anal sexual intercourse with another person, forcibly and/or against that person’s will; or not forcibly or against the person’s will where the victim is incapable of giving consent because of his/her youth or because of his/her temporary or permanent mental or physical incapacity.

Sexual Assault With an Object is the use of an object or instrument to unlawfully penetrate, however slightly, the genital or anal opening of the body of another person, forcibly and/or against that person’s will; or not forcibly or against the person’s will where the victim is incapable of giving consent because of his/her youth or because of his/her temporary or permanent mental or physical incapacity. An object or instrument is anything used by the offender other than the offender’s genitalia. Examples are a finger, bottle, handgun, stick, etc.

Forcible Fondling is the touching of the private body parts of another person for the purpose of sexual gratification, forcibly and/or against that person’s will; or, not forcibly or against the person’s will where the victim is incapable of giving consent because of his/her youth or because of his/her temporary or permanent mental incapacity.

Source: The Handbook for Campus Safety and Security Reporting from the U.S. Department of Education, February 2011

Today, there are three known Title IX complaints filed against Temple.

This issue is widespread among universities across the country, showing no trends to why one school is on the list, and another is not. The students we’ve spoken to and the Climate Survey from the president’s task force showed us a majority of students aren’t familiar with Temple’s formal reporting procedures. There’s uncertainty about Temple’s resources and how to use them. This project is a comprehensive answer to those questions.

Staff members and reporters interviewed students, faculty, staff, nurses, survivor advocates, survivors, administrators and Temple Police to try to understand the process of reporting and how survivors can seek help. In more than a dozen interviews, countless hours with survivors and nearly five months of reporting, we now understand how the university addresses sexual violence, specifically sexual assault, among students, faculty and staff. “100 miles of unpaved road” outlines the system in place for survivors to get support, and the personal experiences of those who have been a part of that process.

“100 miles of unpaved road” was a phrase told to us from one of those people, a rape advocate. She described a survivor she met years ago as such, as a woman who had endured something traumatic, with a road to recovery ahead of her. But this “unpaved road” can mean much more than just how a survivor feels in the moments following an assault. This project outlines the system in place for survivors to get support—a road that is progressing, with work that still needs to be done.

In that five months of reporting, The Temple News found:

- There are currently three Title IX complaints filed through the Office for Civil Rights that are in ongoing investigations. One of these complaints was given to The Temple News from the complainant.

- The university has the proper institutions in place to support survivors and provide education to students about consent, sexual misconduct and sexual violence, however many—if not all—of these offices are underfunded and understaffed, administrators say.

- During the 2014-15 academic year, 20 students were expelled or suspended from the university. Of those, five were expelled because of violations of Temple’s sexual assault policy. In 2014, there were nine reported cases of sexual assault.

- The system in place, described by multiple administrators as “points of entry” into the system of reporting and support, can be confusing for someone in crisis, survivors say; some have suggested a more centralized approach.

We have heard the stories of four survivors, whose experiences will appear throughout this project. Their stories are powerful—but they’re not the only ones. Their voices speak to their own experiences, and not the experiences of all survivors at Temple, or on any university campus. To read detailed accounts of two of these survivors’ stories, click here. These stories include details that may be triggering for some readers.

The Current State

Last year, 4.7 percent of students on Main Campus reported an incident of sexual penetration—as defined by the Wellness Resource Center as vaginal, oral or anal penetration—without their consent.

Nearly 44 percent of students who have experienced sexual assault said reporting was not helpful, according to a climate survey conducted by the Presidential Committee on Sexual Misconduct.

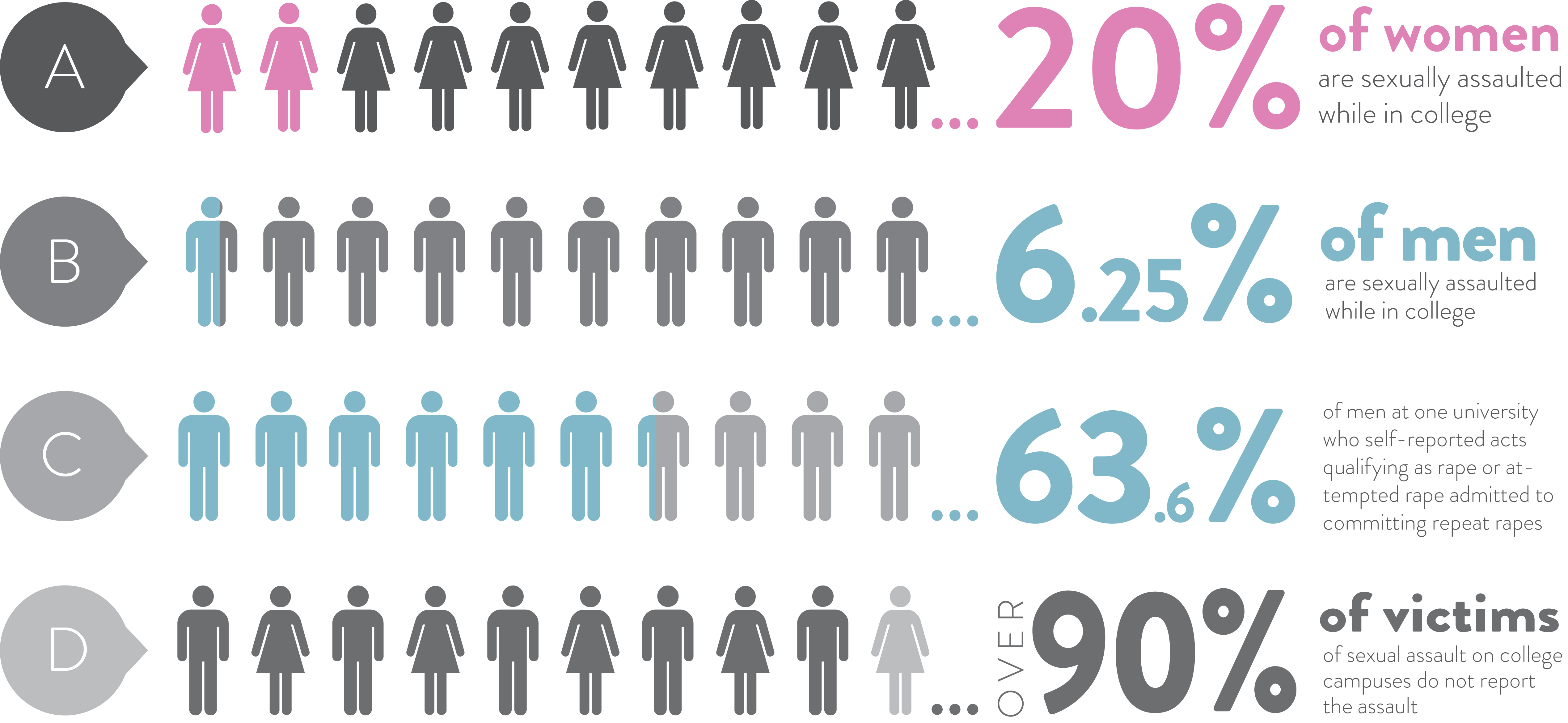

Nationally, 27 percent of college women have reported an experience of some form of unwanted sexual contact, and almost 38 percent of female rape survivors were first raped between the ages of 18 to 24, according to the National Sexual Violence Resource Center.

A spokesman for OCR provided a statement saying the office’s policy was not to discuss details of complaints. When an investigation concludes, it will be disclosed whether or not OCR found Title IX violations at the university—or if there was insufficient evidence, the statement said.

Sandra Foehl, the university’s Title IX coordinator, said she could not recall details of specific complaints. At least one of the complaints, she said, involved an after-the-fact dispute over whether or not sex was consensual.

The OCR requested copies of years of university records to review Temple’s handling of sexual misconduct, Foehl added.

As part of the investigation, OCR visited Main Campus in 2014 to conduct focus groups to ask if students were aware of the sexual harassment and misconduct policies and how to report misconduct.

Foehl said answers “ran the gamut,” ranging from “people who had no notion that we have any of these things, to very informed individuals.”

Harmony-Jazmyne Rodriguez arrived on Main Campus as a liberal arts student in 2013. She filed a Title IX complaint that year, in which she alleges that the university mishandled her sexual assault case.

Rodriguez recounted parts of her more-than-80-page complaint to The Temple News last month as she did late in 2014. She said administrators did not accommodate her request to change housing to get away from the dorm room in which she was raped in August 2013, and further alleged that the Wellness Resource Center declined to assist her because she is a trans woman.

“I am told that they help students in need. But they didn’t help me,” Rodriguez said. Her complaint includes emails from WRC staff asking her to return to their office and encouraging her to involve Campus Safety in her efforts to report.

In her complaint, Rodriguez faults a Student Conduct administrator for disclosing details of her rape to The Temple News that blamed alcohol as a cause of the assault. She said opinion pieces focusing on drinking as a cause of sexual assault made her uncomfortable.

“It was excruciating to have people focus on drinking as a cause of rape rather than rapists,” she wrote.

The complaint is still being investigated.

The most recent reports of sexual assault on or near Main Campus include an incident in late September, when a 20-year-old female student reported to Philadelphia Police she had been sexually assaulted by someone she did not know on Carlisle Street near Jefferson.

Temple, SEPTA and Philadelphia police all collaborated in the investigation to find the suspect, which led to the arrest of Shakree Bennett in mid-October.

More recently, an 18-year-old female student reported a Feb. 13 sexual assault late in March. The student told Temple Police she was inappropriately touched by a 22-year-old male unaffiliated with the university. The student did not want further involvement with Temple Police, said Executive Director of Campus Safety Services Charlie Leone.

In 2014, there were seven reports of forcible rape on-campus, and two that occurred off campus.

In September 2014, President Theobald tasked Laura Siminoff, dean of the College of Public Health, with organizing a task force to investigate sexual misconduct on campus and provide recommendations.

The task force included faculty, students and administrators who met mostly during September 2014 through February 2015, Siminoff said. The group reviewed the university’s current resources and policies and surveyed students’ perceptions of leadership, policies and reporting related to sexual misconduct, according to the official report which was released in April of last year. It also compared best practices around the country and gave administration an idea about what students saw as a problem.

Of 3,763 student survey responses, 58.3 percent of respondents agreed or strongly agreed they knew where to get help if they experienced sexual misconduct and 37.6 percent said they agreed or strongly agreed that they knew Temple’s formal procedures to address complaints of sexual misconduct.

“A lot of different students are unclear about what sexual misconduct is and what rises to it,” Siminoff said.

The task force was a “one-time thing,” she said, adding that it will be up to Theobald if he wants it to reconvene.

In August 2015, President Theobald approved four of the task force’s recommendations:

- the creation of a new website focusing on sexual misconduct

- requiring all students to participate in mandatory, annual online sexual-misconduct awareness training

- updating the Student Conduct Code

- improving the infrastructure of resources and services allocated toward the issue

“Think About It: Part 3,” online training implemented by the Dean of Students, was a starting point for education about sexual misconduct, Siminoff said.

“It can’t hurt, it can only raise awareness,” she said. “It’s not the only solution, but we have to have good education in order to make any real changes. … Big schools are more challenged with how to do this with everybody.”

The evolution of sexual assault policies on Main Campus

The first documentation of an official sexual misconduct policy at Temple was in 1992.

Peter Liacouras was university president, and announced an “interim policy on sexual harassment” in January of that year. Before then, the policies were scattered in various forms and documents throughout separate colleges at the university.

University historian James Hilty said Liacouras was a major reason Temple started implementing policies on sexual assault.

Almost two months after the adoption of the interim policy, a high-profile sexual assault case involving a former student started at City Hall.

The Temple News reported March 4, 1992 that a 20-year-old female student accused Matt McGraw, son of former Phillies pitcher Tug McGraw, of sexually assaulting her at Temple Towers on Sept. 17, 1991.

The case concluded that day, when the jury deliberated for 45 minutes and found McGraw not guilty of sexual assault, the Inquirer reported.

Later that year, the university adopted its first official policy on sexual assault on Sept. 10, 1992. The policy included definitions of sexual assault, information on education and prevention programs and ways to informally and formally report. Liacouras, Temple Police, administrators and faculty formed a committee on the issue.

Following a mandate in a 2011 “Dear Colleague” letter from the Department of Education, the university broadened its policy to include domestic and dating violence, and stalking. It also required schools to include state consent laws in policy.

For the most part, the policies have not changed since the original version in September 1992. Harrison said the university plans to have at least part of the current policy rewritten by the fall semester, with a complete version done by Spring 2017.

“Lawyers wrote these policies initially, which are difficult to understand, so we want to move away from that,” she said. “This has been part of a shift across the county, to make the policies clearer.”

Marina Angel, a law professor who helped draft the original sexual assault policy, believes the university needs a central office to handle sexual harassment and assault.

She added Temple’s policies need to be rewritten by knowledgeable faculty members, not members of university counsel or the provost’s office.

-Steve Bohnel

Dean of Students Stephanie Ives said the decision to use “Think About It: Part 3” was because it “seemed consistent” with the other two installments of the training. “Think About It: Part 1” is sent to incoming students in August, before arriving on campus. “Think About It: Part 2” is a follow-up for freshmen, given in October.

Ives said some students were “really angry” about the mandated training. Foehl, who oversees training for faculty and staff, said there was pushback as well.

“No, I do not think it’s enough,” Ives said. “I think it’s one way to ensure that all of these students in so many different locations get consistent educations.”

For Valerie Harrison, the resources for sexual assault survivors at Temple are adequate, but the coordination of those resources is lacking.

The task force agreed, and now she shares a floor with President Theobald as the centralized resource to help survivors get help. Since being hired in March, she is responsible for advising the President Theobald for compliance issues—including sexual assault—as a part of a three-person department.

Andrea Seiss, the current senior associate dean of students, will serve as the university’s new Title IX coordinator responsible for “services” and “systems” related to sexual misconduct beginning June 1.

Seiss’ responsibilities will include working with Harrison and making sure policies are “up to date and user-friendly,” defining what sexual misconduct is on Temple’s campus, ensuring compliance with federal guidelines, explaining to students the resources available for education, prevention and support.

“As time has passed, we’ve come to realize there’s more that we can be doing and should be doing for students. That’s where this position has come from,” she said.

“A university of this size … you can’t have one person doing that,” she added.

This summer, Seiss will begin reforming current university policy on sexual assault, connecting other resources on campus and assisting investigation.

“It’s going to be an area that’s going to continue to evolve through what we learn from students, faculty, staff, families, as we get talking more,” she said.

“We [have to] take advantage of confidence of our best practices, so that we are better coordinated and hopefully at the end of the day for our students, that would mean our resources and information are more easily accessible and you know where to go. You don’t have to go to five or six different places to get an answer.”

Kimberly Chestnut, director of the Wellness Resource Center, said this office is closer to her vision of a “victim advocacy center,” which has not previously existed on Main Campus. Chestnut imagines a confidential reporting office that could also offer all the necessary resources to survivors of any kind of sexual violence.

“That role doesn’t really exist here,” Chestnut said. “I think it would be an incredible asset.”

Addressing sexual assault or mishandling of sexual assault was on many platforms of tickets running for Temple Student Government for the 2016-17 academic year.

Title IX on campus

Title IX was perhaps the most significant and groundbreaking portion of the Education Amendments of 1972, experts say. Broadly, it prohibits gender-based discrimination in education, and outlines several areas in which colleges and universities must ensure fairness.

Sandra Foehl is the university’s Title IX coordinator and director of its Office of Equal Opportunity Compliance. When she was hired in 1973, Foehl’s job largely focused on promoting and ensuring gender equity in the admissions and financial aid processes and in athletics. She was also there to encourage women’s involvement in STEM fields.

1980 was a turning point, when the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission pronounced that sexual assault and harassment prevention were required to be in compliance with federal law. Prevention, training and policy review soon became part of Foehl’s job.

Around this time, Foehl, university lawyers and faculty women grew more involved in university policy. Women’s issues committees in the Faculty Senate and the union met regularly to offer input for the university’s sexual harassment and sexual assault policies.

“The faculty women wanted to be involved. They were the ones who would hear the reports of students being harassed by peers and by faculty,” Foehl said.

-Joe Brandt

Take TU, a group comprised of student-activists Tina Ngo, Jared Dobkin and Isabella Jayme, said their campaign was the only intersectional-feminist campaign, and prioritized sexual assault as the most important issue facing the Temple community.

Ngo said she experienced an abusive relationship during her freshman year at Temple that affected her studies and well-being. She should have enough credits to be a junior, but she said she struggled academically due to the trauma that followed the relationship.

Ngo said she didn’t report the incidents of assault at the time, even though some of the reportable action happened on Main Campus in her dorm, because she wasn’t sure of the implications of reporting and what an investigation would mean.

Eventually, Ngo said, she reached out to Temple Police who put her in touch with Gray. After talking with her, Ngo sought counseling at Tuttleman Counseling Services, but she couldn’t get an appointment for about a month. The experience, she said, was draining.

This process led Ngo and her team to propose the idea for a sexual assault crisis center on Main Campus. The ticket identified the currently overworked staff in mental health resource centers, lack of clear information about reporting and a lack of serious education for students about what sexual assault is and how to handle it.

“I would literally have no idea how to report,” Jayme said. “I can’t even remember what we were told during orientation. There has to be more people who don’t know where to go.”

Ngo said “Think About It: Part 3” is not even close to what the university should be doing. A lot of students, she said, do it just so their account won’t be put on hold.

“These types of learning exercises need to be taken outside of the computer. It needs to be addressed with students face-to-face,” she said.

Any campus event can be an opportunity to talk about and educate on the topic of assault, Ngo said. She thinks Temple Student Government is responsible for addressing these issues and implementing ways to improve.

Ngo said the center should also be available to community members and should be a single place where any survivor can go get any help they may need.

“It’s just a room, that’s all we need,” Ngo said. “We just need a place where victims and survivors have one place they can go and get the help they need and know how to report.”

One of the priorities for the student group Student Activists for Female Empowerment, or S.A.FE., is having a resource center for sexual assault survivors on Main Campus. As of February, the group has spoken with administration once this school year and is focused on bringing attention and improvements to resources.

“I think Temple would like to portray that we have a lot of resources for this,” said Taylor Davis, the group’s vice president. “The ones that we do have, they’re just not communicated well enough to the student body at large.”

The Fight to Inform

It is nearly pitch black in the basement. The air is stale and the floor is sticky. People pack in tight, elbows folded against sides to keep cups from sloshing over. The music throbs like an irregular heartbeat. Using the backlight on their phones, boys scrutinize the bodies of other party-goers in the darkness.

It’s a familiar scene, played out a thousand times across Temple’s campus and surrounding areas. The address changes, but everything else—the sickly sweet jungle juice, the wafting smell of marijuana, the roaming hands, the lingering eyes, the unspoken expectations—stays the same.

In 2015, 32.9 percent of respondents to the Wellness Resource Center’s Annual Report said they consumed five to six drinks or more the last time they “partied/socialized.” And 30.1 percent of those students said they “pace drinks at 1 or fewer per hour.”

“Some of these behaviors are—not some, most—are influenced by drugs and alcohol,” said Kevin Williams, the director of residential life on the nature of sexual assault.

Every assault, however, is different. According to the National Sexual Violence Resource Center, 75 percent of self-identified sexual assault perpetrators reported using alcohol before the incident. The report also includes the addition of alcohol into sexual assaults are “much more likely to include attempted or completed rape than incidents without alcohol.”

For Williams and the assistant director of residential life, Shondrika Merritt, sexual assault too often occurs in tangent with parties, drinking and alcohol in relation to residential life. Williams and Merritt, as well as the rest of the residence life team, often partner up with the Wellness Resource Center and Campus Safety to promote education and sexual well-being among students who live in these facilities.

According to the Climate Survey conducted by the president’s task force, which was released last April, 41.7 percent of respondents indicated they received training on policies and procedures concerning sexual misconduct. The rest of the respondents said they had not received training and or were “unsure.” But all freshmen receive training at orientation and online before arriving. The numbers were nearly the same regarding prevention training.

“How do we help them become aware of themselves, how they interact with others and the responsibility to be part of a larger community?” Williams said. “A lot of that is about self-responsibility, knowing what’s acceptable, what’s not acceptable, teaching someone who maybe didn’t have this in high school what are expectations here at Temple.”

We have to be very sensitive about this. There are some times when we might have an event and step in and say, ‘I think we might need to do some education around this, can we see a bulletin board go up?’ Can we see an email go out to the floor or to the building to say, ‘Hey, I know this is impacting you, let’s talk about it.’ Shondrika Merritt<br />

Assistant Director of Residential Life

I think we have to continue to figure out how we educate 40,000 students on multiple campuses, not just on how to make healthy decisions, but what are the resources? Kevin Williams<br />

Director of Residential Life

But aside from these programs, Williams said the majority of prevention education takes place in orientation and at residence halls.

“Our programs build from where orientation leaves them off,” Williams said.

As a survivor, Caroline said she thinks incoming students need more direct information about consent and the risks of binge drinking.

“There needs to be a better education, especially to incoming freshman,” Caroline said. “We’re told that it’s wrong, and then you go to police, and it’s not wrong. … It’s not what I always thought it was.”

Before taking on their roles during the school year, resident assistants undergo training sessions on handling sexual misconduct in August, which prepares them for counseling and communication with survivors.

Instruction on how to properly report an assault is also delivered through the Wellness Resource Center, which educates RAs on the different forms of sexual assault and how to spot potential instances. Winter training is also mandatory for RAs, as are Wednesday staff meetings and bi-weekly, one-on-one sessions to address flaws and collect feedback on how each floor is handling issues.

In recent years, Williams said, RA training for handling assault has been tweaked to be more “intentional,” emphasizing communication with the survivor about what steps will be taken once an assault is reported. This strategy, Williams said, reduces anxiety for the RA and creates a more personal and less intimidating atmosphere for the survivor.

“You’re going to go to who’s familiar,” Williams said of many survivors’ crisis management. “You see the RA every day, you have had maybe some intimate personal conversations, or you may have not, but at least you know they are there for you when these things come up.”

But even with the education, training and expectations set by orientation and residence life, things can—and do—go wrong. Tara Faik, campaign manager for Take TU, which ran in the 2016 Temple Student Government elections, said cases go unreported because many people don’t recognize assault when it comes from someone they know.

Eight out of 10 survivors of rape were intimate partners with the person who sexually assaulted them, according to the National Sexual Violence Resource Center.

“There are huge cultural and systematic ways in which the mistreatment of women is supported,” the Wellness Resource Center’s director, Kim Chestnut said.

“To truly root out some of the things that perpetuate assault means to address issues of sexism, and misogyny, and objectification of women, and all people because it’s not only women who are assaulted and that we have to work on the way in which we culturally socialize our entire population about the way we value other humans, and particularly the way we value women,” she added.

Chestnut said there may be a perpetuation of “rape culture” among the different communities across campus that students may be involved in.

“How do the communities we have on campus perpetuate those things?” Chestnut said. “Like very commonly Greeks and athletics where there is a lot more opportunity to have a patriarchal structure that just has some different historical messaging about the ways that you can do these things.”

As the president of the Temple University Greek Association, Daniel Roper understands the “black eye” pertaining to the association between Greek life and sexual assault, and said it is an issue that cannot be ignored.

“It’s something that we always address and know that there’s a stigma out there with Greek life that we are trying to say, ‘This isn’t us. This isn’t who we are,’” said Roper, who sends information on sexual assault and its misconceptions out to Temple’s 28 fraternities and sororities to combat the issue.

Rather than formal training, which he said would be difficult to accomplish “because every case is different,” Roper favors bringing in guest speakers and partnering with campus organizations to help fraternity and sorority members learn about the topic.

One requirement for students joining a fraternity or sorority is attending a New Member 101 session— a “crash course” on Greek life for new members, Roper said. Sexual assault isn’t the focus, but is brought up during the orientations.

Some of the responsibilities for education fall on individual sororities and fraternities. The groups often send representatives to national conventions, where they can discuss how chapters on other campuses are tackling the issue.

“I’ve heard people say, ‘Well, obviously rape is bad, I’m not one of those people,’” Isabella Jayme, former candidate for Take TU’s vice president of external affairs said. “It’s kind of like—‘I wouldn’t do it, so there’s no problem.’”

This issue, however, is still prevalent on Temple’s campus and nationwide. For Williams, that became clear with the Title IX investigation, which put the university on the map—and not in the most flattering way.

All seven reported incidents of rape from 2014 occurred in residence halls, according to Temple Police.

“People [from OCR] came in,” Williams said. “They talked to us. We were investigated. … A lot changed and a lot changed fast, and I think for the better. It said, ‘Universities, you’ve got to wake up.’ We want to make sure we’re putting students first and providing the best support we can.”

Williams and Merritt have attended national trainings and regional trainings—a new expectation of both their roles.

The Clothesline Project

Other programs like the Wellness Resource Center’s Clothesline Project and the annual Walk a Mile in Her Shoes event help teach students these expectations as well.

“Clothesline is broadly about all forms of violence,” said Morgen Snowadzky, the assistant to the director at the Wellness Resource Center. “But a lot of what we focus on, because we do it during Domestic Violence Awareness Month and Sexual Assault Awareness Month, is sexual assault and domestic violence.”

The Clothesline Project has been held at Temple twice each academic year during October and April for about the past eight years.

As part of the Clothesline Project, survivors decorate T-shirts with messages about their personal experiences of violence or abuse, and allies likewise decorate T-shirts with messages of support.

Keeping in line with the national program of the Clothesline Project, each differently colored shirt signifies a different experience. For example, a purple shirt indicates someone has been attacked due to sexual orientation or gender identity.

However, students are free to choose whichever color shirt they would like to decorate regardless of messaging.

Snowadzky said she has attended the Clothesline Project at Temple for seven semesters.

“Every year I am struck by the language, by the power, by the terrible things that people have been through,” Snowadzky said. “Things that are like, ‘Friendship is not consent,’ ‘Just because we’re friends doesn’t mean you get to assume that we can have sex’—I think things like that, that when people see them on T-shirts it gets them to think.”

“And so that’s kind of the role of that event: to get people to be aware that it’s happening, it’s happening to people on our campus and hopefully, to learn from some of the shirts,” Snowadzky added.

-Jenny Roberts

But does Temple still have room to improve?

“Absolutely,” Williams said. “I think we have to continue to figure out how we educate 40,000 students on multiple campuses, not just on how to make healthy decisions, but what are the resources?”

“I think Temple’s administration really needs to take serious the resource aspect of sexual assault,” added Davis, vice president of S.A.F.E. “The statistic is real, one in four women in college will experience sexual assault and those stats are way too high to rely on Philadelphia to accommodate us.”

Davis said she decided to help start S.A.F.E. because of the number of people in her life who have been affected by sexual assault.

S.A.F.E. holds its support group every other week and focuses on support and awareness. The organization also collaborates with other groups like WOAR and Childhood Emancipation and participates in events like the Clothesline Project, Take Back the Night and March to End Rape Culture.

S.A.F.E. believes sexual assault is something that the general student body doesn’t discuss because it seems “taboo” and the processes for reporting cases are not clear.

The residence life office tries to make sure students know what happens once they report an assault to their RA. A sexual assault isn’t something a member of residence life can keep to themselves, Merritt said.

After reporting to an RA, professional staff are called in to make sure the student’s current needs are met and to work through what the next steps are, dependent on whether or not the student wants to make a police report about the incident.

Of course, Merritt and Williams hopes it never goes that far. Instead, they hope the education and prevention of sexual assault can occur at the hall level.

There is little point in duplicating big initiatives created by other groups on campus, Merritt said, but there are “scattered programs” throughout the year held by RAs that “hit on the topic” of sexual assault. But even those have to be handled carefully, Merritt added.

“We have to be very sensitive about this,” Merritt said. “There are some times when we might have an event and step in and say, ‘I think we might need to do some education around this, can we see a bulletin board go up?’ Can we see an email go out to the floor or to the building to say, ‘Hey, I know this is impacting you, let’s talk about it.’”

Moving forward, both Williams and Merritt need students’ help.

“How students feel here, that I don’t know yet,” Williams said. “And from the data we do collect, I feel like students feel safe, I feel like they think we’re moving in the right direction, but I feel like we should be doing more for specific groups. And how then are we working with the Asian community, the black community, around these issues? Because it’s not just one paradigm that fits everything. So I’m looking for that.”

Making the improvements they have so far and continuing to move forward, however, is not always easy—despite 10-and-a-half years on the job, Williams still has days where his work takes an emotional toll.

“I would be naïve, to think we’re never taking this home,” he said. “Probably like many of you, I call my mother. I don’t give details and I say, ‘This is what we’re going through, I just need to hear your voice.’ And that helps.”

The System

At Temple, resources are spread out across Main Campus, disjointed and independent.

The system has several different offices that can help start the process of support, and can serve specific, immediate needs for a survivor.

The Temple News found that if a student is assaulted on, near or off Main Campus, there are several resources or “points of entry,” including, but not limited to:

- Special Services Coordinator Donna Gray

- Tuttleman Counseling Services

- Women Organized Against Rape

- Campus Safety Services

- Special Victims Unit and Philadelphia Sexual Assault Response Center

- The Wellness Resource Center

- Student Health Services

Each office can start the process of reporting or seeking professional support. Instead of one center for psychological, medical, emotional and criminal support, it’s designed to allow survivors to choose where they are most comfortable seeking help first.

The Climate Survey from the president’s task force said more than half of the respondents reported they knew where to get help for sexual misconduct on campus, but less than half agreed or strongly agreed that they knew Temple’s formal reporting procedures.

Valerie Harrison, the new adviser to the president for compliance issues is expected to streamline the process by “centralizing” the university’s efforts to provide support.

“Victims of sexual assault are not the same and don’t respond the same,” Harrison said. “So for some, they may not be comfortable reporting immediately, and we have to recognize that and accommodate that.”

“[We have to] allow them to be who they are and to navigate the process at their own pace in their own way,” she added. “We’re just there to support them.”

“Temple should make it really clear what avenues you can take,” Taylor Davis, S.A.F.E.’s vice president, said. “Whether you choose to first call the police and file a report right away, or if you want to go to the hospital and start a medical exam, or if you really just want some crisis counseling.”

The Navigator

Her office, located across from Mitten Hall next to Saxby’s Coffee, has windows on three sides. Her desk gives her a view of passersby and the entrance to Polett Walk. But on a particularly sunny day, it’s almost impossible to see who’s inside.

“We try to be very intentional in terms of creating a good atmosphere so people feel they can come in and they can talk,” Gray said. “It’s nice because it allows for openness, without like, ‘Oh my god everyone knows I’m in here.’”

Over the course of a semester Donna Gray said she has about 30 conversations with individuals on campus concerning sexual assault. Her role allows her to be a “liaison” between survivors looking for resources, education, to start the criminal process with police or file a report with Student Conduct.

Charlie Leone said Gray is “on the front lines” and helping survivors “navigate” through Temple’s system. Her main role is to connect survivors to other resources, on or off Main Campus. With the priority of explaining a survivor’s options, Gray said she has gone to court with a survivor, attended Student Conduct hearings and regularly helps survivors file reports with Temple Police.

In terms of reporting a case to police in order to pursue the case criminally, Gray said often it can take years to resolve, meaning an underclassman could file a case that may not be resolved by their senior year.

Caroline said she wouldn’t have come back to Temple to finish her degree in psychology if it weren’t for Gray and her support.

“Mainly just knowing that there’s somebody there that understands and knows everything and knowing that I can text her or call her if I need to come see her anytime,” Caroline said. “She saved me here. I really don’t think I could have finished at Temple otherwise.”

“I think the scariest thing is, you don’t want people to feel like they’re alone in it,” Gray said. “You don’t want somebody to feel like, ‘I went through all of that, and what for?’”

She added that sometimes police may tell a survivor that even though they want to pursue a case criminally or through Student Conduct, there is not enough evidence.

“Oftentimes we have a tendency to think … ‘It’s all about the victim and the victim gets to decide,’” Gray added. “The reality is that, it’s not. It’s the district attorney’s office, as well as the officer, the detective.”

For Caroline, it was up to the District Attorney. In her report, she told officers she had no recollection of the physical assault.

“I didn’t realize who he was or anything,” she said. “But what I know now is it took place at like 3 or 4 in the morning, in my bedroom.”

“My whole being for the last year has been focused on the hope that he will go away, and I will never have to think that he didn’t get what he deserved,” she added. “But he won’t pay for this. And the law needs to change, really, is what needs to happen.”

“Typically there is going to be a degree of anger, and that’s understandable and frustrating,” Gray added. “Sort of feeling like, believe it or not, the system has failed in some way.”

A confidential office

For survivors in need of support, Tuttleman Counseling Services, the university’s free, confidential counseling center, has a team dedicated to helping survivors of sexual assault known as the Sexual Assault Counseling and Education Unit. The SACE Unit has existed for 23 years, and is currently made up of seven counselors, including Coordinator Aisha Renée Moore.

“We generally provide crisis intervention, advocacy, counseling and referral services for students who’ve survived things like sexual assault,” Moore said.

In addition to Moore, SACE is composed of an assistant coordinator and five trainees who can also provide services to students dealing with partner violence, stalking, sexual harassment and childhood sexual abuse.

For students hoping to address any of these concerns, one of the benefits of accessing Tuttleman Counseling, Moore said, is confidentiality. Tuttleman Counseling is one of the few offices on campus that is not required to report a sexual assault to Campus Safety Services. Kim Chestnut called all other offices on campus—besides Tuttleman Counseling and any clergy on campus like the Newman Center or Hillel at Temple—“mandated reporting offices.”

Moore said having a confidential office can allow a survivor to receive more information about the resources without committing to filing a police report or following up with Student Conduct.

To begin receiving counseling for sexual assault or to find out about other resources available on campus, a student must come to the center during walk-in hours, which vary by day. A student must sign in at the front desk and fill out paperwork, including a mood assessment form called C-CAPS. After that, the student can see a therapist in the center.

Last year, about 3,100 students used Tuttleman Counseling Services’ walk-in hours, Moore said.

Sarah Trotta, assistant coordinator of SACE, said the therapist will then conduct an assessment “to get a better understanding of the level of risk, the urgency of what’s going on and to provide a first intervention,” if the student is coming to the counseling center as a survivor.

During these walk-in appointments, called a “triage appointment,” survivors meet with whichever counselors are available, which may not be a counselor in the SACE Unit. But all Tuttleman counselors are equipped to offer help to survivors, Trotta said.

Counselors discuss medical, safety and criminal justice concerns with survivors and present them with resources and options to further pursue action within these avenues if they so choose. Counselors also address substance-use concerns, eating concerns, risk of homicide and risk of suicide.

Survivors are then seen back at Tuttleman Counseling by a SACE Unit counselor within two business days of the initial walk-in appointment for an urgent intake appointment, Moore said.

“We make room in our schedule for our SACE urgents,” Moore said. “So whatever’s happening, room will be made and we will meet them without fail in that timeline.”

White-Walston oversees WOAR’s preventative education and awareness programming for all students in Philadelphia, all the way from children in pre-K to college students. She’s been a guest lecturer for Temple’s Human Sexuality class and has co-facilitated workshops in dorms on Main Campus with the Wellness Resource Center.

When working with student survivors of sexual assault, White-Walston said WOAR’s job is to operate “parallel to university services.”

“WOAR is a resource outside the university,” she said. “Sometimes students don’t want to go to the university’s health services. They want complete anonymity, so they can come to WOAR.”

WOAR assists survivors throughout a process of healing. When a survivor initially goes to the hospital or SVU to receive treatment, the survivor can be accompanied by an advocate from WOAR, who will help them understand various treatment and legal options. Some hospitals will automatically offer the survivor access to an advocate, but in other hospitals, the survivor must request an advocate independently. Additionally, the survivor can call WOAR’s 24-hour hotline to receive immediate help from an advocate.

Advocates are especially important because they provide survivors with information that some hospitals don’t, White-Walston said. For example, some Philadelphia hospitals will not automatically offer survivors pregnancy or HIV prophylaxis, an immediate preventative treatment to prevent a person from becoming pregnant or HIV positive, and a WOAR advocate can recommend a patient ask for those services when they are not immediately offered.

Laquisha Anthony is a volunteer advocate for WOAR and founder of an organization called Victory Over Inconceivable Cowardly Experiences, or V.O.I.C.E., which strives to empower survivors of sexual assault through processes like one-on-one workshops, anger management classes and awareness events.

Anthony got her start as an advocate with WOAR long after she was sexually assaulted herself, as an undergraduate at Kutztown University of Pennsylvania. After Anthony was assaulted, she didn’t tell anyone. They only found out after she realized she was pregnant about two months after the incident.

“I know that I’m helping someone to not go through what I went through,” she said. “That’s what being an advocate is for me: standing up for someone who isn’t in a position to do so themselves. Standing beside them, and doing it with them.”

Following the initial treatment, WOAR keeps in close contact with the survivor to help them receive regular counseling, which can be done on-site in WOAR’s office at 1617 John F. Kennedy Blvd, Suite 1100.

White-Walston said she thinks a rape crisis center on Main Campus would be a positive step for the university.

“To enhance what’s there is not a bad thing,” White-Walston said. “If you do expand your center, it says that student safety is a high priority.”

But Anthony said she’s not sure a centralized rape crisis center is the best way to maintain the privacy of survivors.

“If someone sees you at that location, then everybody kind of knows,” she said. “I think that’s the downside of having one particular situation. It could be beneficial, but it could be harmful at the same time.”

In the future, White-Walston hopes to continue to see prevention programming incorporated into Temple’s battle against sexual assault.

“If you only address it when something happens, it’s already too late,” she said.

“I would shout in front of millions of people if I had to,” Anthony said. “What I’ve been through is not in vain.”

Reporting an incident

Charlie Leone says underreporting of sexual assault is a problem. But when he sees an uptick in reporting, there’s no way to know if it’s because of an increase in crime, more education or more awareness on campus.

According to the National Sexual Violence Resource Center, more than 90 percent of sexual assault victims on college campuses do not report incidents of sexual violence.

2015 saw a decrease in sexual assault cases. These trends are complicated, and often rely on more than one variable, he said.

Leone said if a survivor comes to the police to file an initial report they do not have to pursue the case criminally or through Student Conduct. Some survivors, he said, can file an anonymous report, under a “Jane Doe” but include details surrounding the incident like location, time and nature of the assault.

“We try to talk to the person and see, ‘What do they want?’” he said. “Of course from our end, we are always thinking of prosecution, evidence, that kind of thing. But there is also another side of us that we know there is other things that the person needs.”

“You have to handle this the way you want to handle it, and it doesn’t necessarily include reporting,” Olivia said.

Filing a report through Temple Police starts when an initial call is made. From there, an officer will ask the survivor a few basic questions, Leone said.

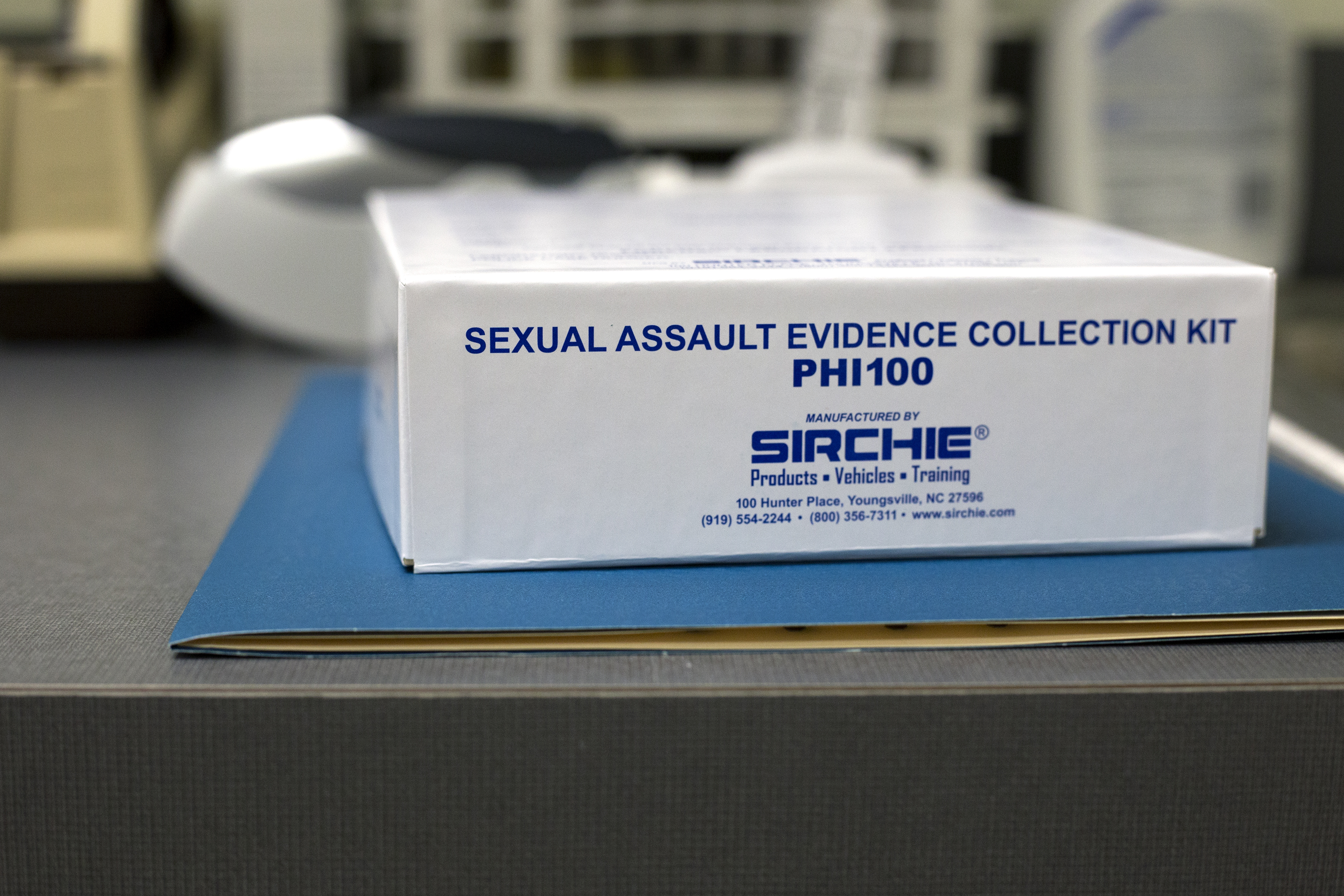

An officer will generally meet with a survivor to complete a report. From there, Temple Police will notify the Special Victims Unit in Hunting Park. An investigator from SVU will review the case and notify Temple Police if the survivor should come to their facilities for further questioning and to have a rape kit

In some cases, the call from SVU will not occur until days after the initial report to Temple Police.

When Olivia saw Donna Gray months after she was raped, it wasn’t until a few days later that Temple Police called her and—despite her protests—took her to the Special Victims Unit.

“I was like, ‘I have a lesson, I don’t want to do this right now.’ And she was like, ‘Well you have to go now,’” Olivia said.

And it wasn’t only like that with police. Weeks after her initial report, she was notified by Student Conduct that the university was investigating her case. When she was called in for a meeting, it was explained to her that she would have to tell her story to a panel of faculty members at a hearing with the perpetrator.

At the time Olivia would have brought the case to Student Conduct, the university utilized a student panel to hear cases. After the 1960s, Senior Associate Dean of Students Andrea Caporale Seiss said, it became “best practice” for a student to tell their story in front of their peers in Student Conduct matters. Two years ago, Student Conduct adopted a board of administrators and faculty members for sexual assault cases, and then in August 2015, Student Conduct hired former Supreme Court Justice Jane Cutler Greenspan to hear all cases.

For officers to best handle situations with survivors when filing reports, Leone said the department has “customized” training that involves equipping officers with all of the information they may need to refer a survivor to another office. These skills include interview techniques, knowing when an individual may not want to disclose certain information, referring resources and educating them on the reporting process at Temple, Leone said.

“Right now, [officers are] doing well,” he said. “We want them to be sensitive in these types of environments. Especially talking to someone who has been through a horrific experience.”

From her experience, Tina Ngo said she believes police aren’t properly trained to deal with the emotional side of responding to assault, and that sensitivity training could be used across the board throughout the process. She said often, she felt like she was the one to blame during the reporting process and in seeking mental health help.

After Temple Police had notified SVU and given the information from the report to the Dean of Students or any other “points of entry” offices that may need it, like Student Conduct, police are no longer involved. Leone said he will often divert survivors to other resources on campus after police have finished reporting.

“It’s not just us here,” he said. “It’s a group of us.”

The facility for Philadelphia

Inside the facility at 300 E. Hunting Park Ave. sits four different units: the Department of Human Services, the Philadelphia Children’s Alliance, the Special Victims Unit and the Philadelphia Sexual Assault Response Center.

The facility is a place for survivors of sexual assault to report incidents of assault to SVU detectives and have medical examinations conducted.

Olivia’s experience on Hunting Park Avenue was brief. She said she told a detective her story, one that occurred more than two months prior and with little evidence.

“He ends it, and he goes, ‘Well, so this is a very gray-area case and nothing is going to happen,’” Olivia said. “And I was like, ‘Why am I here then?’ He said, ‘Well, you know, it would be really good if there were more people who brought up these gray-area cases, even if you lose cases like this, they are really important.’”

“Is this like you want me to be some kind of martyr for other victims?” Olivia said. “What is going on here?”

Since the incident occurred months prior, Olivia did not have a rape kit conducted. In some cases, however, if the survivor consents, a Sexual Assault Nurse Examiner is called to the facility. It takes up to an hour for a SANE to arrive for an examination.

When a SANE arrives, Mike Boyle, the center’s program director, said they ask for consent to conduct a private and sometimes internal examination. If the survivor agrees—including signing a document to affirm—the nurse will inform survivors if she sees any injuries that are “probative,” Boyle said, and, if she receives consent, will photograph those specific injuries, like bruising and broken blood vessels.

Anne Marie Jones is a SANE who has been working at PSARC since December of 2014. Last year, she conducted 103 examinations.

Jones said before a SANE starts collecting forensic data—also known as a rape kit—they will ask for urine samples for a pregnancy test, an oral swab for HIV testing and an initial DNA swab. At PSARC, Jones said nurses cannot conduct any sexually transmitted disease testing or Pap testing, but can offer prophylactic medications to prevent survivors from contracting STDs they may have been exposed to like gonorrhea, chlamydia, trichomoniasis, bacterial vaginosis as well as a five-day starter pack for HIV testing.

Following this testing, SANE nurses will conduct a brief interview. These questions include details on the type of force used in the assault like choking, kicking or punching, and if there was ejaculation during the assault. Boyle said this is more like a “checklist,” and less like a “narrative” to reduce any kind of bias in a nurse’s report.

The story behind the center

Until 1977, the Philadelphia Sexual Assault Response Center didn’t exist. Survivors of sexual assault were treated at Philadelphia General Hospital. When the hospital closed in ‘77, rape exams in Philadelphia were split between Thomas Jefferson University Hospital for people living on the south side of the city and Temple University Episcopal Hospital for the north side. These hospitals were known as “Code R.”

In 2005-06, Mike Boyle, currently the center’s program director and only full-time staff, said WOAR hosted the Sexual Assault Advisory Committee, which proposed a center that would take survivors out of emergency room waiting rooms and crowded hospitals that would take hours to even see a survivor.

“Most rapes don’t result in a traumatic injury that would require emergent care,” he said. “But as a result of the tradition of going to a hospital, you’re going to be triaged. … Rape victims could have waited easily six hours before they were even seen [at the emergency room], so the process then begins of doing the exam and the interview. That’s a very tiresome, tiresome and anger-provoking situation. Especially since we knew there was nothing the emergency room was going to do.”

A committee within the SAAC was formed in 2008-09 to draft an idea of what a rape crisis center could look like and how it would work. At the time, Ralph Riviello, now the PSARC’s medical director, was an attending physician at Hahnemann University Hospital and a professor at Drexel University College of Medicine. He proposed the idea to the college’s dean to back this resource center, and he liked the idea, Boyle said. The center opened in May 2011.

-Emily Rolen

From there, the nurse will swab the patient based on information collected in the interview as part of the rape kit. This can include an internal exam to look for injuries and collect DNA.

Inside a rape kit—which is initially supplied by the police department and funded for examination by the city—are envelopes. Each has a label, like “rectal swabs,” “vaginal swabs,” or “blood sample,” and contains two Q-tips and cardboard tubes to preserve the evidence. This examination will take about an hour to an hour-and-a-half, Boyle said.

Jones said she tries to stay professional while conducting the exam and doing the kit.

“When they start breaking down and crying and starting to hug you, then it can be a little tough sometimes,” she said. “But you can’t really show emotion. We’re supposed to be in control and professional and we’re their first support and to comfort them, but there’s a line. You can’t be a friend.”

“They’re all professional and worked in various capacities in medical settings: in emergency rooms, on medical floors, so they’ve seen a lot of sadness,” Boyle added.

“This is just part of the job.”

‘I just want to check in’

Kim Chestnut said her role with the Wellness Resource Center is just that: providing resources.

Chestnut said any student is “welcome” to come in and get information or support around any topic of concern. For a survivor, she said, there are a multitude of options.

“Ultimately we say, ‘You have lots of options and you are in control,’” Chestnut said. “‘So, let me offer you what you can do moving forward and you decide what feels best to you.’ And so that could just be accessing medical and therapeutic support, it could be moving forward with wanting to do a police report. It could just be moving forward through with a conduct, internal Temple report. It could be nothing: ‘I just need information. I don’t need anything else, I just want to check in.’”

The Wellness Resource Center, she said, sees one or two survivors a month and more traffic in the fall semester than in the spring.

When Harmony-Jazmyne Rodriguez came to the WRC in the days following the night she was raped, she said no one in the office was ever available to see her.

As far as filing a report on campus, Chestnut said she “can imagine it would be helpful to students.” She said she supports a “victim advocacy center” on campus that would be more “thoroughly resourced.”

“As we currently stand, one entity can do certain things, but not really as one human are we capable of being a confidential reporting destination and providing all interim measures for a student that was assaulted,” she added.

Chestnut said the possibility of this is “under review” as part of the task force recommendations. She said additional reporting and investigation was needed from the university. So, hopefully that would provide “all that [President Theobald] needs.”

At the WRC, there is a team of students who serve as peer educators, known as the Health Education Awareness Resource Team. The assistant to the director of the WRC and the teaching assistant for HEART’s peer educator certification class, Morgen Snowadzky, said the educators lead “peer-facilitated programming” for events held by student organizations and resident assistants throughout the year, as well as for in-class presentations. These programs address sexual assault, as well as topics like relationships and alcohol education.

In addition to programming centered around education about sexual assault, HEART peer educators also assist survivors of sexual assault through resource referral and one-on-one consultations.

The survivor would then be matched up with a peer educator who is comfortable talking about sexual assault and provide the front desk with a list of topics they are most comfortable talking about with students in advance.

“So people will come in and be like, ‘I have this question,’” Snowadzky said. “First, we figure out, ‘Do you need like a doctor, or like a therapist? Or do you just want someone to talk to?’”

If a survivor requires more assistance after this consultation, HEART peer educators may connect the survivor with a member of the WRC’s professional staff to further pursue accommodations or to start an investigation with Student Conduct.

Snowadzky emphasized that while their office offers resource referral for survivors, its main goal is sexual assault prevention through bystander intervention.

“Ideally, in our world, we would be doing enough interventions that the rate of sexual assault would go down so the support services would be less necessary,” Snowadzky said.

“We’re looking to support people after the fact,” she added. “But we’re really looking for prevention, empathy and awareness.”

Seeking medical attention on Main Campus

Twenty years ago, Mark Denys worked as an ER nurse at Albert Einstein Medical Center, one of the designated rape crisis centers in Philadelphia before the creation of the facility on Hunting Park Avenue.

As a man, he was often not invited to assist in conducting a rape kit. His experience with survivors, however, is something he still remembers.

“I was often with the survivor before they would go for the examination, or after,” he said. “And it’s different every time. Sometimes they don’t want to talk and they don’t want to share anything, other times they’re sharing everything and telling you everything. So it’s really different for every person and the situation and what happened.”

Denys is one of the only administrators on campus who has extensive knowledge of what occurs at the Philadelphia Sexual Assault Response Center. This center, he said, helps keep evidence collected consistently, decreasing the chance for variables to interfere.

Creating a resource center like PSARC on Main Campus would decrease “hurdles” for survivors, he said. Nurses that specialize in conducting rape kits, SANEs, do not currently travel to Student Health Services.

“From a resource standpoint, it would be great for our students not to have to travel someplace, so I think from that standpoint it would be great … because it took a lot for them to come here, or go to Tuttleman Counseling or call Campus Safety, and then this is just one more hurdle to go over to go there, but again, they are the experts. It’s something we don’t do a lot. We may see one patient a month, we may see one patient every two months. And then we could have three in one month. We don’t see the volume that we become experts.”

“I want survivors to be in the care of experts,” he added.

If a survivor comes into Student Health Services looking for medical attention, Denys said a nurse can provide them with prophylactic medication and emergency contraception. They will also test for any sexually transmitted diseases. If the assault happened the night before a survivor comes in for an appointment, Denys said nurses will call the survivor back in a few months to be tested again.

“I wish more would come to us earlier and sooner, and for whatever reason, either they don’t know about us or they don’t know what to do,” Denys said. “Often times we may hear about it even six months later sometimes. They come in for their annual exam, and it’s ‘Oh, by the way, last September this happened to me.’”

Denys’ first concern at Student Health Services is to make sure survivors are “medically stable,” and that there are no critical medical concerns when they come for an appointment. After staff ensure that, they will connect the survivor to other offices on campus. Denys has drawn up a brochure that he hopes to display in their offices, listing each office and what service it can provide for a survivor.

If someone comes in for an appointment and identifies themselves as a survivor, a nurse will take back the patient right away “so there is no waiting,” Denys said.

“From the time we know, it’s only a few minutes until we get them in the room,” he added.

Moving Forward

Olivia and Caroline are current students at Temple University. In order to maintain their anonymity, certain details about their identity, the perpetrators and the incidents have been withheld. The Temple News’ Editor-in-Chief sat down with both women on multiple occasions and transcribed their experiences.

These are their stories.

Olivia

It was her second semester of freshman year, and Olivia was partnered up with a senior for a small ensemble in the Boyer School of Music.

“We were kind of feeling each other, so we talked for a couple of hours afterwards, and he was like, ‘Can I take you out sometime?’”

They went to dinner, they kissed and she told him that she was seeing other people. She wanted to be honest with him, she said.

“And I said, full disclosure, ‘I am sleeping with other people. I’m open to things happening, but I’m seeing other people.’ And something clicked in him and that was weird and I noticed it and I ignored it.”

After the date, he took her back to his house. He lived alone on Berks Street, far from her dorm in 1300 Residence Hall.

“It was kind of implied that things were going to go in the sex direction. And it started to get kind of weird. I just noticed that he was angry, or something was off, and he was just not happy with something. He offered me a glass of wine, and I accepted. And he brought over the wine, sat on the couch with me, and I had a sip of the wine and then he like jumped on me, kind of. And I was like, ‘I don’t know how into this I am.’”

He suddenly picked her up and moved her into his bedroom, where he would rape her.

“I was clear. I said no. And I was like, ‘Well, we’re pretty far out on Berks, I’m a freshman, nobody really knows where I am, he lives alone, there’s nobody who was in the apartment. And it’s like, almost midnight.’

I stopped him again, and I said, ‘Aren’t you gonna put on a condom?’ And he like made a noise. Like a discontent noise. And put one on.

I was trying to rationalize it the whole time, like, ‘Maybe it’s fine. Maybe this is OK.’ He was getting rough, and I was like, ‘Calm down. Stop.’

I knew that it was bad when I said something like, ‘Don’t you wanna be patient and enjoy it?’ And he was like, ‘Considering that I’ve wanted to rip your clothes off since you got in here, I’ve been patient.’

After I realized that this was something that was intentional, and something that was going to continue happening because this person was over 6-feet tall and I’m a 5-foot-tall girl, I shut down. And then I slept there.”

In the morning, he walked her back to her dorm and asked her if they were going to have a relationship.

“He asked me what we were doing, and I was like, ‘Nothing. Nothing.’ And then he was still mad, and left. I went up to my roommate and I just told her that I had a weird night and this guy sucked in bed. And I didn’t know what else to do.”

After she was home, she said, she responded differently than she had anticipated.

“I mean, I took a shower. I know all the stuff. Don’t take a shower, go get a rape kit. In hindsight it’s so weird that I did not ever expect myself to respond that way. I thought, ‘I’m an empowered woman and I know about feminism and I know about standing up for myself,’ and I did not follow any of the advice I would have given a friend.”

A week after the assault, Olivia and her rapist had to perform together in an ensemble.

“At the end of the concert we were all at the reception and he pulled me aside, and he was like, ‘Can we talk?’ And I was like, ‘Talk about what?’ And at this point I was in complete denial. And he was like, ‘I felt like you led me on, I thought we were going to have a relationship.’ … I looked him in the eye and I said, ‘You should have stopped when I said no, you should have used a condom when I told you to use a condom and I have no respect for you. I have nothing else to say to you.’ And he said, ‘Well I guess we’re done here,’ and walked away from me.”

It was two months until she told anyone about the assault.

“I felt so afraid to be in the music school. Everybody knew both of us. I was afraid that I was going to turn the corner in the empty basement and, you know.

I felt like I was losing my mind, so I thought, ‘Well, Temple has free therapy,’ so I went.”

The therapist she saw at Tuttleman Counseling kept telling her she was “articulate” when detailing the account of the rape, and that she was “recovering well” and “very resilient,” she said. But Olivia said she didn’t feel right. The counselor suggested she go to Temple Police, but she didn’t want to press charges, instead hoping to file an “incident report,” she said. Eventually, she decided to see Special Services Coordinator Donna Gray to learn about more resources for support, and to file a report that would help other women if this were to happen with the same man again.

Olivia had a meeting with Gray in her office.

“I told her very clearly, I said, ‘I don’t really want to press charges. I would like to file a report, but I don’t want to press charges. Because I don’t want to go through a jury. What I would like to do is, if somebody has a case against this person or opens up a case against this person, I would love a report filed so that, I’m not the only person or that person isn’t the only person. But I have no evidence.’”

A police officer came into Gray’s office, and she told her what happened to her, including her full name, his full name and details of the assault in the report.

Olivia left the meeting with the understanding that her involvement with police was over. Gray told her someone might contact her for more information, but she was “probably done.”

“About a week later I get this phone call from [a woman] and she goes, ‘There’s a police car waiting for you outside of 1300 and you need to go.’”

Temple Police was taking her to the Special Victims Unit in Hunting Park to file a report with a detective. With little choice, Olivia rode with a female officer in the front seat of a police car to SVU, where she was interviewed.

“I went in with a male detective, and he said ‘If you want to stop at any time you can,’ and I was like, ‘Well I’ve told my story a bunch of times before, I guess I’ll just do it again.’”

After the interview, the detective told her the case wouldn’t go anywhere because it was a “very gray area case.”

“And I was like, ‘Why am I here then?’ He said, ‘Well you know it would be really good if there were more people who brought up these gray area cases, even if you lose cases like this, they are really important.’ And I was like, ‘Whoa, is this like you want me to be some kind of martyr for other victims? What is going on here?’”

She left SVU without filing the report with police, and was taken back to campus.

A week or so later, she got another call from Gray with more news.

“She said, ‘So, [the perpetrator] has been notified that there are charges pressed.’ … And I asked her like, ‘Why did this happen? What’s going on? … This person knows where I live, knows where I work, my friends, they know my schedule, they know where I go to school, they know when my classes are.’”

Gray’s response was that Olivia had misunderstood the process of reporting. Her initial report with police, she told her, had been sent to SVU and Student Conduct, and the investigation process through the university had already begun. But even today, Olivia still doesn’t know if Student Conduct told the perpetrator it was her who filed the report, or if it was anonymous.

“She said, ‘Temple has the final say on Student Code violations.’ And I said, ‘So, I didn’t want to press charges, so I am not pressing charges, but Temple is pressing charges.’

It just wasn’t up to me, and I was never made aware.”

About a week later, Olivia received an email from Student Conduct about a meeting. When she arrived, it was explained to her that Temple has the eventual say whether or not they want to file a misconduct case, she said.

“It felt like it was very self-serving for Temple and they were just going through the motions. And they hear this all the time and my case isn’t unique, which, that’s not how a person should feel. That might be true, but I shouldn’t have felt that way.

So Temple knew that I didn’t want to press charges, but it was up to them to override that.”

At her meeting with Student Conduct, she said she was finally explained the process of how Temple hears the cases and how the process works. She signed a paper saying she was not going to testify at the hearing, and was promised she was done with the case. As she was leaving the room, she was told she had to wait for a police escort because her rapist was in the waiting room on the other side of the door.

“It felt as though I was talking about something I had no choice in and I felt like I needed justice for, and I had no choice in that. I had no choice in my justice system, either.

I like to consider myself a good communicator and I like to consider myself capable, and for me to miss something—like,‘Temple presses charges whether or not the student wants us to, it’s our decision’—was never communicated.

At the end, I was so done with this whole thing. That was the last interaction I had.”

After the assault, Olivia said she wasn’t interested in joining a support group, but was just looking for a way for her and other women to feel safe from the perpetrator. She needed a way to “ensure” that she wouldn’t have to see this person, she said. It made her “constantly afraid” to go on campus.

“I still feel like I’m going to go into the basement of Presser and be at my locker and I’m going to turn around and this person is going to be there. It’s not unreasonable.

I blamed myself a lot because I was like, well, I knew I was going to see this person regardless, even if we had consensual sex, I still would have seen him around. So I blamed myself for this uncomfortableness that I felt. And it hasn’t gone away.”

She described her urge to press charges against the perpetrator as a “soup of conflict,” being torn between not wanting to “label herself,” but wanting people to know it happened to her, and it could happen to them.

“Just today, every once in awhile, I’ll still get nervous if I think about it too hard. … That’s what makes it so difficult. Being so educated on all of this makes it even harder. How could this happen to me, an educated, independent, strong-willed person? Does that mean that I’m not those things? No is the conclusion, but it kind of still feels that way.

I kept questioning, ‘Is it just me? Is it just that this is how I’m interpreting it?’ There was so much guilt and questioning of myself in this whole process because I had trusted processes like this up until this point. It made me feel like absolute trash, like I had no say in anything. Things were just happening to me.

It felt like everybody in the world, all of a sudden, knew. And I had no control. After I went to this seemingly private conversation with Donna Gray where I supposedly just knew that, OK there’s a little folder with my story in a drawer so if somebody comes in and says, ‘[He] did this thing to me,’ [police] can … look him up. That’s all I wanted. For there to be multiple stories. …That would make more sense than me pitted against this person.

But as soon as I told my story, it wasn’t mine anymore.”

Caroline

“I was drunk. It was in my apartment. I didn’t know the person, at all. Nobody knew the person.”

Caroline was a sophomore at the time, hosting a party with friends north of Main Campus with her roommates. They had parties before, and this was no different. That night, they left the door unlocked so no one would have to keep letting guests in.

“I think that probably was what happened, was that someone was just walking by. It was two guys together. They were not students, and they came in. At that point it was really late in the night, so nobody thought twice, like, ‘Who are these people?’”

Caroline said it was at about three or four in the morning when one of two men, who she would later learn from Philadelphia Police were not Temple students, raped her in her bedroom. She does not remember anything during the assault, but she remembers waking up after.

“I remember waking up and I was still kind of drunk, and I didn’t have the same pants I had on. … I had my period, and I had had a tampon in. And he took it out of me. And I just didn’t feel like everything was OK. I went downstairs and my roommates were awake and they all thought I had remembered, and they said it was really loud, and I just kind of froze. And it was like, at first, ‘Wait, what do they mean?’ And I didn’t really understand it, and then I thought about it for a second, and was like, ‘Wait, if I don’t remember this, then I never agreed to it.’

I don’t remember wanting to at all, I mean, I didn’t want to. And again, I’m not the type of person who would even have a one-night stand, not that there’s anything wrong with that. I just know in my heart that I wouldn’t have done something like that. And even if you are that type of person, that doesn’t make it OK, either.”

The next morning, she called her parents and returned home to Connecticut. It was there that she called police and went to a hospital for a rape kit.

“That’s just something you never ever want to have to do, you know?

Nobody is prepared to know that this happened to someone they care about. My whole family was devastated. But I think it’s really important to remember that the statistics say that this happens to one in four or five women our age, so really you probably already know somebody who this happened to. And I know personally, I know two people who this has happened to. It’s not talked about enough. And the more that we talk about it, the more people will realize it’s not OK. ‘Cause it’s just not.”

While she was home, her parents contacted Temple and Philadelphia Police, hoping to file a report. Since the incident occurred outside Temple Police’s jurisdiction, she filed the report through Philadelphia Police. Officers have since identified the alleged perpetrator. Since then, Caroline has been waiting for more answers.